Background

The 51st North Carolina arrived in Charleston on July 11, 1863. The next day, the regiment was ferried across the harbor to Morris Island, where the soldiers garrisoned Battery Wagner. Six days later, on the 18th of July, the Fifty-First fought off a furious Federal assault on the small fort.

The Tar Heels left Morris Island the day after the Yankee attack. The 51st North Carolina went into camp on Sullivan’s Island. The men returned to Battery Wagner twice before Union siege operations forced the Confederates to abandon the fort on September 6, 1863.

Life on Sullivan’s Island was hard on the soldiers of the Fifty-First. Bad food, bad water, and bad weather took a toll on the men’s health. Weakened by the poor living conditions, the men fell victim to typhoid fever, dysentery, and malaria. Doctor Morrisey, the regiment’s surgeon, was kept busy tending to the sickly men.

The Surgeon

Doctor Samuel Bunting Morrisey, a practicing physician in Robeson County before the war, was appointed the 51st North Carolina’s surgeon on May 1, 1862. The 32-year-old doctor had his hands full caring for the regiment’s 900-plus soldiers. He had to screen dozens of men each morning during sick call, sorting the slackers from the truly ill. With little medicine on hand and under pressure from the brigade commander to limit furloughs, Dr. Morrisey was forced to send most of his sick to nearby hospitals.

The General

Thomas Lanier Clingman was an attorney and politician before the war. Clingman had served in the North Carolina General Assembly and the U. S. House of Representatives. He was a U. S. Senator when North Carolina seceded from the Union. Clingman served as colonel of the 25th North Carolina before using his political connections to receive a brigadier general’s appointment. He was assigned to brigade command in late 1862. The brigade consisted to the 51st, 8th, 31st, and 61st North Carolina Regiments.

The Feud

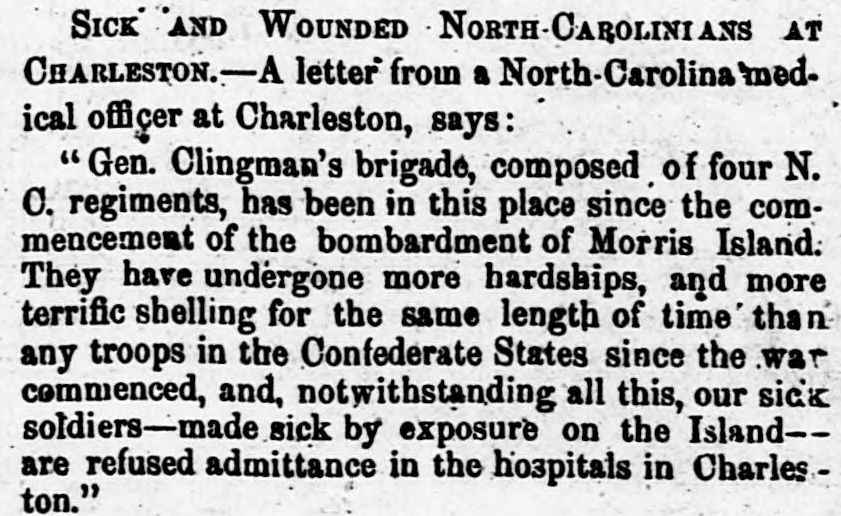

While the 51st North Carolina was suffering on Sullivan’s Island, a dispute erupted between General Clingman and Doctor Morrisey. In early August, Morrisey was alarmed to hear from a South Carolina counterpart that the hospitals in Charleston had started refusing patients. The Charleston doctors had instructed the South Carolinian to furlough sick solders from his unit, rather than send them to the hospital. Doctor Morrisey was sending about fifty of his soldiers to the hospital each month. As the brigade’s senior surgeon, Morrisey felt he should take action. He sent a letter to North Carolina’s Surgeon General informing him of the situation in Charleston and asking if the State could open a hospital in South Carolina for the care of Tar Heel troops.

Someone leaked the content of Morrisey’s letter to the press. An acquaintance of General Clingman, Samuel Biddell, wrote to the general and told him about the story in the papers. On August 15, Clingman replied to Biddell in his typically combative style, denying that Charleston hospitals were refusing to treat North Carolinians. “If you can give the name of any Surgeon making such a statement as you refer to, I have no doubt but that he will soon find himself disgracefully dismissed from the service,” wrote Clingman. The general went on to accuse the person who was making the “false statements” of “working in behalf of the Abolition miscreants who are laboring to exterminate our people.” Biddle, of course, sent Clingman’s response to a newspaper.1

Now it was Doctor Morrisey’s turn to be angry. After sending his letter to the Surgeon General, Morrisey had discovered that the directive to furlough soldiers only applied to the one South Carolina unit. Learning that his North Carolina men would still be treated at the Charleston hospitals, Morrisey dismissed the matter until he became aware of General Clingman’s letter. Morrisey fired off a letter of his own to the general demanding an explanation for his comments, “which I knew was calculated to reflect very seriously upon my character.” Clingman responded apologetically, stating that he was not fully informed about the situation when he wrote Biddell. In his response, Clingman refers to Morrisey as “an able and efficient army Surgeon” and “a gentleman of integrity and good character.” The surgeon was mollified by General Clingman’s reply. Morrisey sent both letters to the newspapers, and the dispute came to an end.2

1 Wilmington Journal 3 Sep. 1863.

2 Wilmington Journal 15 Oct. 1863.