NOTE: I am reposting this article. For reference material supporting this post, see Analysis: Swift Creek, May 9, 1864.

The Problem with Sources

While researching The Honor of the State, I came across an interesting article in the May 17, 1864 Daily Confederate. The article, copied from the Petersburg Express, describes the rout of a New Hampshire regiment at Swift Creek on May 9, 1864. The regiment was attacked and routed by two companies of the 51st North Carolina. Just two companies routed an entire regiment!

The Daily Confederate story is summarized in North Carolina Troops‘ unit history of the Fifty-First. The incident was also briefly referenced in a letter published in the Wilmington Journal on June 2, 1864. I thought this was a spectacular story, so I included it in the book.

Too bad it isn’t true.

The Newspaper Account

The Petersburg Express reported that two companies of the 51st North Carolina chased a New Hampshire regiment two miles on the night of May 9. The source of their information was a Yankee prisoner who had come into the Confederate lines the same night. The prisoner related that the New Hampshire unit, numbering 800 men, had been assigned to picket Brander’s Bridge, on the far right of the Union line. The Tar Heel companies were dispatched to induce the New Hampshire men to “change their base.”

At 11:30 p.m. the Tar Heels snuck up on the Yankee pickets and fired a volley. The Yankee infantry, shocked by the surprise attack, failed to respond. The North Carolinians fired two more unanswered volleys. The blue coats ran, pursued closely by the Rebels.

A running fight followed. The Tar Heels pursued their foe for two miles. It was a bright starlit night, and whenever the Federals stopped to regroup, the North Carolinians fired into the dark mass. Each volley was answered by the screams of the Yankee wounded. The chase ended when the New Hampshire regiment reached the safety of the main Union lines.

On June 2, 1864 the Wilmington Journal published a letter from “Will” (probably Captain William Norment of Company F), a soldier in the 51st North Carolina. In the letter, Will recounts how Companies E and F “fought a Regiment off and on one whole night…” while the Fifty-First was at Swift Creek.

Fact Checking the Petersburg Express

The Petersburg Express reported that “a heavy picket guard, consisting of a New Hampshire Regiment, amounting to 800 men,” was stationed at Brander’s Bridge. The regiment “was somewhat isolated.” This information was relayed to the newspaper by a “Yankee who had come into our lines.”

The 3rd New Hampshire was sent to reconnoiter Brander’s Bridge late in the evening on the 9th of May. They were about two miles from the extreme right of the Union lines. The regiment mustered a little over 700 men. Private Henry Smith was reported as deserting on May 10. So far, so good.

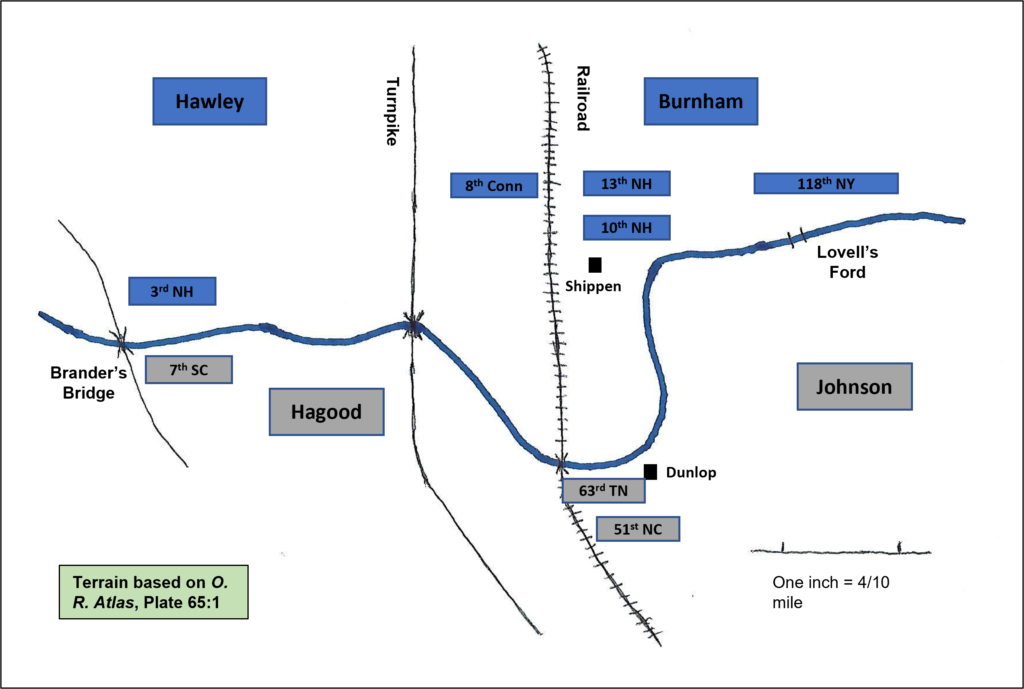

But then the Petersburg Express story starts to unravel. The article continues by stating that two companies of the 51st North Carolina charged the New Hampshire regiment and sent it running. The Fifty-First was over three miles away from Brander’s Bridge. The 7th South Carolina Battalion and an artillery battery were posted at the bridge.

Colonel Josiah Plimpton, commanding the 3rd New Hampshire, reported that he ran into a small Confederate force, supported by artillery, near the bridge. After a few minutes of skirmishing, Plimpton withdrew to a line he had established 700 yards north of Swift Creek. He reported no further action that night.

Although the newspaper story accurately describes the 3rd New Hampshire’s situation, the 51st North Carolina did not attack that regiment.

What Really Happened

Late in the afternoon of May 9, a Union battery (Hunt’s) unlimbered near Shippen’s House, about 3/4 of a mile from the railroad bridge across Swift Creek. The 10th New Hampshire, part of General Hiram Burnham’s brigade, was posted 400 yards behind the artillery. The battery began shelling the Confederates on the opposite side of Swift Creek. The Confederates responded by sending sharpshooters to the left of the battery. “Being considerably annoyed by the enemy’s sharpshooters,” General Burnham ordered two companies of his own sharpshooters, armed with Sharp’s rifles, “to drive the enemy out or silence their fire.”

Now General Bushrod Johnson, on the south side of Swift Creek, became “very much annoyed” with the Yankee marksmen. They were firing from behind a fence about 600 yards from the Confederate lines. Johnson ordered the 63rd Tennessee to drive the enemy soldiers back.

Around 8:00 pm, Colonel Abraham Fulkerson, commanding the 63rd Tennessee, sent two companies across Swift Creek to drive the enemy sharpshooters away. The Rebel infantry charged the Yankees and drove them back to the Shippen House. The 10th New Hampshire advanced and halted the Tennesseans. The Rebels withdrew to their lines.

Confederate reports do not mention any more fighting after Fulkerson’s Georgians drove the Union sharpshooters back. However, Union accounts describe two more Rebel charges during the night. The first occurred around 11:00. The Confederates charged the Yankee pickets and drove them back toward the Shippen House. The 10th New Hampshire “charged in turn upon the enemy, drove them back in confusion, and re-established the picket line in its original position.”

A final Rebel charge occurred at an unspecified “later hour.” This charge was stopped within 50 yards of the 10th New Hampshire. After “a spirited skirmish,” the Tenth once again drove the enemy back to their lines.

What Might Have Happened

Two companies of the 51st North Carolina relieved the two companies of the 63rd Tennessee at “a late hour of night.” The two Tar Heel companies were likely Companies E and F, as mentioned in the Wilmington Journal. These two companies might have made the final two charges on the Union skirmishers. There is no evidence that the 51st North Carolina was involved in any fighting that night, other than the flawed Petersburg Express account and the letter from “Will.” You decide.

Epilogue: Coughlin’s Medal of Honor

Lieutenant Colonel John Coughlin (later breveted colonel and then brigadier general) commanded the 10th New Hampshire at Swift Creek. On August 24, 1893, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on the night of May 9, 1864. The citation reads: “During a sudden night attack on Burnham’s Brigade, resulting in much confusion, this officer, without waiting for orders, led his regiment forward and interposed a line of battle between the advancing enemy and Hunt’s Battery, repulsing the attack and saving the guns.”

Copyright © 2021 – 2026 by Kirk Ward. All rights reserved.