Gillmore’s First Attempt

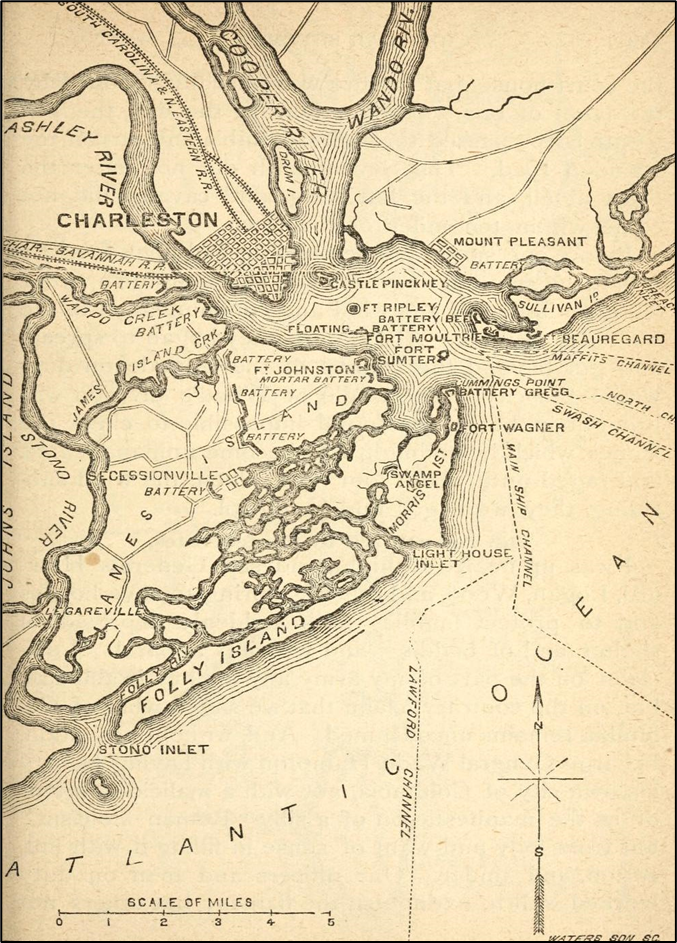

In June of 1863, Major General Quincy Adams Gillmore was assigned to command the Union’s Department of the South. Gillmore was a respected Regular Army engineer. A few months earlier, he had masterminded the siege and capture of Fort Pulaski near Savannah. Utilizing the superior range and accuracy of the navy’s newly deployed rifled cannon, Gillmore was able to force the fort’s surrender without making an infantry assault. The fall of Fort Pulaski isolated Savannah and ended that city’s usefulness as a Confederate port.

General Gillmore expected to follow his success at Savannah with the conquest of Charleston. Gillmore kicked off the effort on July 10 with an assault on the southern end of Morris Island. The Federal troops made good progress initially, driving the Confederate defenders up the island. The Union advance was halted at Battery Wagner. The Federals assaulted the fort the next day, but the attackers were repulsed with heavy losses.

Gillmore realized that Battery Wagner could only be captured by a determined infantry assault preceded by a massive artillery bombardment. He spent the next week constructing artillery positions on the south end of Morris Island. By July 17, the Union had moved twenty-five rifled guns and fifteen siege mortars to within range of the fort.1 Union engineers constructed defensive works for infantry across the island, approximately 200 yards in front of the battery nearest Wagner. These works, later referred to as the First Parallel, were roughly three-quarters of a mile from the Confederate fort.2

Battery Wagner

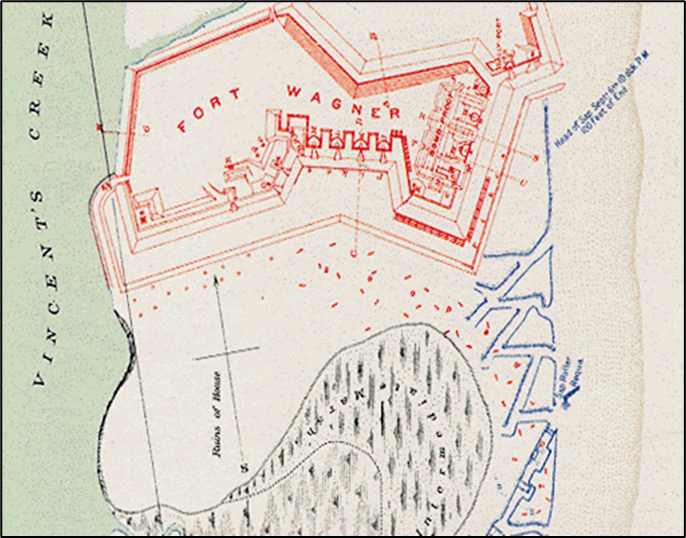

Confederate engineers chose a location for Battery Wagner where Morris Island narrowed to only 250 yards, allowing the fort to span nearly the entire width of the island. The battery was bordered by Vincent’s Creek on the west and the Atlantic Ocean on the east. The fort faced southward, with an impenetrable marsh about 200 yards from the south wall. The marsh constricted the approach to the fort to a strip along the beach less than fifty yards wide at high tide.3

Battery Wagner was built out of materials at hand on Morris Island. The walls were constructed of palmetto logs and sandbags covered with sand and earth. This type of construction turned out to be extremely effective against Union artillery. Solid shot would merely bury itself into the sand walls, and a hole made by a projectile was immediately filled by loose sand.

The fortification was 630 feet at its widest (east to west) and because of its irregular shape, ranged from 80 to 215 feet in depth (south to north). The sloped rampart was thirty feet high and topped with an infantry parapet. The western part of the interior contained a one-acre parade ground. North of the parade ground, against the interior of the wall, were the garrison’s quarters. A sally port, near the northeast corner, provided access to the fort through the north wall.4

The south wall measured 600 feet from corner to corner. It consisted of bastions on the east and west corners, connected by a 200-foot curtain. Four artillery pieces, protected by heavy traverses, were positioned in the curtain. The west bastion mounted three guns that could provide enfilading fire against an assault on the curtain. A sea coast mortar was situated in the southwest corner of the bastion.

A bombproof magazine sat behind the western end of the curtain. This magazine provided a seaward traverse for the guns in the western bastion. The guns in the curtain and the west bastion were further protected by embrasures.

Two siege howitzers sat in the east bastion. These guns fired over the parapet. They could be turned to defend the curtain, the southern approach, or the sea face.5

From the east bastion, the sea face wall ran northward for 210 feet. The Confederates built a large mound against the interior of the sea face. Three guns were mounted atop the mound to cover the ship channel. The southern end of the mound provided a heavy traverse for the guns, protecting them from enemy fire from the south.

Twenty-foot by twenty-foot magazines were dug out of the northern and southern ends of the mound. A large bombproof, 130 feet long and 30 feet wide, lay under the interior side of the mound.6 The bombproof was designed to protect the entire garrison during enemy bombardments.

The defensive works of the fort were completed by an exterior wall that ran from the northeast corner of the battery, 100 feet up the coast. This wall protected the sally port and the commissary. Two gun emplacements in the wall provided a sweeping fire for the beach front.7

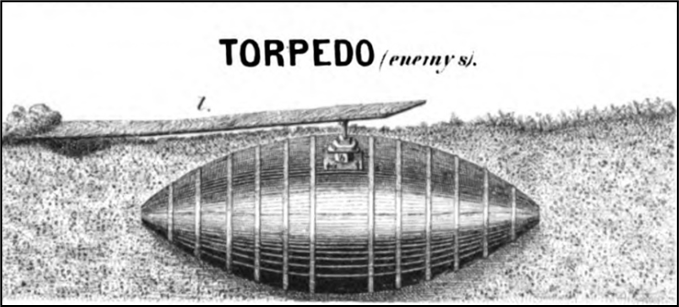

The location and construction of the battery provided the fortification with superb defensive capabilities. Even so, the Confederate engineers added more features to further enhance the fort’s security. The south face of the fort was protected by a moat, ten feet wide and five feet deep, which ran from Vincent’s Creek along Wagner’s south wall to the beach. This ditch was filled at high tide, and sluice gates retained the water. The southeast bastion and the curtain were protected by sharpened palmetto trees angled outward from the bases of the walls. Dozens of primitive land mines were buried directly in front of the fort.8 By the time Battery Wagner was completed, it presented an imposing obstacle for an enemy force attempting to take Morris Island.

The Defenders Get Ready

The Confederates had watched Gillmore’s preparations closely, and by July 17, they knew an attack was coming. On that day, for the first time, some of the Union batteries at the southern end of Morris Island fired on Battery Wagner. The Confederates in the fort hurriedly beefed up their defenses by filling the officers’ quarters with cotton and sand and by cutting a new sally port in the west wall.9

Two sections of field howitzers had arrived at Battery Wagner a few days earlier. Each section consisted of two twelve-pound smoothbores. One pair of cannon were positioned in the gun emplacements on the beach wall. The other two guns were placed inside the fort, near the new sally port.

Brigadier General William Taliaferro, commanding Battery Wagner during this period, assigned his garrison to specific positions on the battery’s ramparts. Three companies of the Charleston Battalion were assigned to the south wall, from the new sally port to the curtain. The 51st North Carolina’s sector began on the left of the Charleston Battalion and continued eastward along the curtain to the southeast bastion. Four companies of the 31st North Carolina were assigned to defend the bastion at the southeast corner of the fort and part of the sea wall running from the bastion northward to the rear sally port. The other two companies of the Charleston Battalion defended the remaining portion of the sea wall down to the beach.10

Regimental commanders assigned each of their companies to a specific area of wall within their defensive sectors. Further, company commanders assigned each of their soldiers to a spot at the parapet. The garrison practiced running to their positions several times during the day. General Taliaferro expected each man to rush to his assigned spot without hesitation when the Federals attacked.

The Rebel defenders inside the fort had done all they could to prepare for an assault. There was nothing left to do but nervously wait for the Yankees to attack.

The 32nd Georgia Infantry was scheduled to relieve the 51st North Carolina on the 18th of July. The North Carolina regiment had already served six hard days at Battery Wagner, performing fatigue duty, and huddling in the bombproof during Union bombardments. Unfortunately, the Confederate command, fearing that a Union assault was imminent, decided to delay the move until early the next morning.11 The Tar Heels’ stay on Morris Island was extended by just one night, but it would be a long, bloody night that the soldiers of the 51st Regiment would never forget.

The Preliminary Bombardment

On the morning of July 18, General Gillmore was ready to assault Battery Wagner.12 He initially decided to make the assault with only Brigadier General George Strong’s brigade. However, after conferring with his staff, he decided that Colonel Haldiman Putnam’s and Brigadier General Thomas Stevenson’s brigades would support the attack. Gillmore assigned Brigadier General Truman Seymour as overall commander for the assault.

That morning, the forty-two guns of the Union land batteries opened up against Battery Wagner.13 As the morning progressed and the Union guns found their range, the firing gradually increased. By noon, the Union fleet, consisting of the New Ironsides, five Monitors and five gunboats, had joined in with another fifty heavy guns. The Federal land and naval gunners subjected Battery Wagner to a furious barrage that continued without pause until dusk. General Taliaferro conservatively estimated that 9,000 projectiles hit the fort during the eleven-hour cannonade. Despite the ferocity of the bombardment, only eight defenders were killed and twenty wounded during the attack.

Battery Wagner had no effective response to the fierce Union bombardment. The artillerists attempted to stand by their guns, and a few infantry companies hid in the surrounding dunes. The Confederates replied to the Union artillery with one shot every ten or fifteen minutes. The mortar was fired every thirty minutes. These responses were more symbolic than anything. The gunners needed to preserve their ammunition for the assault they knew was coming.

As the intensity of the barrage increased throughout the morning, the garrison began to fear that the artillery pieces on the south wall would all be damaged. They needed these guns to beat back the infantry assault that was sure to follow the Yankee fusillade. The four guns in the curtain were dismounted. The field pieces were covered with sandbags. The remaining guns were not only covered, but their embrasures were also stuffed with sandbags.

The shelling was so fierce by noon that the North Carolina regiments crowded into the bombproof. Part of the Charleston Battalion took cover behind the parapets. The rest of the battalion’s soldiers hid in “rat holes” constructed from empty rice casks dug into the sand dunes just north of Battery Wagner.14 The artillerists stood bravely at their positions, using what shelter the gun emplacements afforded.

For the next seven hours, life inside the bombproof was misery for the men hunkered down inside. The ground shook with the explosions of shells and the air was full of dust and smoke. The soldiers stood front to back, shoulder to shoulder in the sweltering heat and prayed for the bombardment to end.

A large flagpole, flying the garrison flag, stood on the rampart of Battery Wagner’s southwest bastion. Around two o’clock in the afternoon, the garrison flag was shot away. Several of the South Carolina troops rushed out and re-hung the flag. Not long after, the pole itself was shattered by an artillery round. Private Gilliand of the Charleston Battalion asked for and received the 51st North Carolina’s battle flag and erected it next to the shattered pole.15 That evening, the Fifty-First’s flag was “torn in four pieces by shell.” Colonel McKethan would not have time to requisition a replacement flag until September.16

At four o’clock, the rising tide allowed the Union Monitors to approach within 300 yards of the fort. Their precise firing dismounted Battery Wagner’s sea face guns, and no Confederates were seen on the ramparts from that time until the bombardment ceased three hours later.

General Gillmore and his staff observed the bombardment throughout the day from a lookout tower on one of the sand hills within the Union lines. The Union artillery appeared to be inflicting a great deal of damage on Battery Wagner. The Confederate artillery had stopped responding, and no Rebel soldiers were seen on the ramparts. The Union commander was confident that the preparatory bombardment had done its job. The assault on Battery Wagner would surely succeed. Gillmore notified General Seymour that all the artillery inside Battery Wagner had been disabled. Furthermore, he estimated that no more than 500 Confederate infantry remained to defend the fortification. General Gillmore ordered the assault to begin at dusk. Seymour formed his brigades behind the First Parallel, a little less than a mile from the Confederate stronghold. Strong’s brigade was in the lead, followed closely by Putnam’s brigade. Stevenson’s brigade was held in reserve.

The Assault on Battery Wagner

The soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts, commanded by Colonel Robert G. Shaw, were chosen to lead the assault. They were lying on the beach, not far north of the Federal breastworks. The men were tired and hungry. The regiment had been roused early that morning on James Island. They spent the entire day moving from James Island to Morris Island. They were first ferried to Folly Island, marched to Lighthouse Inlet, ferried across the inlet to Morris Island, and then marched halfway up Morris Island to the spot on the beach where they now lay. The men had not eaten since breakfast.

While the men of the 54th Massachusetts lay in the sand and waited for dusk, the men of the 51st North Carolina were standing shoulder to shoulder in Battery Wagner’s bombproof. They had been in the bunker for seven hours, enduring suffocating heat with no food and little water. Union artillery mercilessly pounded their fort with a constant stream of shot and shell, shaking the ground and rattling dust out of the bombproof’s roof. The air was thick with smoke, dust, and the odor of 900 unwashed bodies. Several men fainted. The Tar Heel soldiers were eager to leave the vile confines of the bombproof.

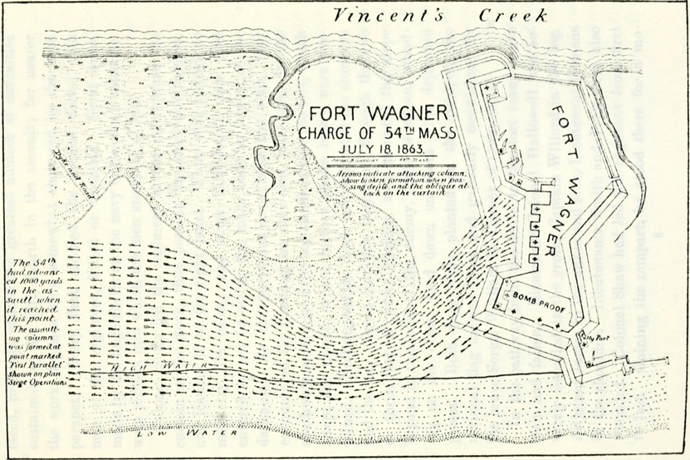

After half an hour, the Massachusetts men were ordered to their feet. Colonel Shaw formed his regiment into two wings, with four companies in front and four companies in rear. Behind them, the rest of the Union assaulting force was forming in columns of companies. Anticipation of the coming charge made the Massachusetts soldiers forget their fatigue and hunger. They warily eyed the silhouette of Battery Wagner, three-quarters of a mile in front of them.

The regiment waited in restless anticipation until the command, “Forward,” was finally given. The first wing stepped off in quick time, followed closely by the second wing. The beach narrowed as the regiment proceeded toward Wagner. By the time the men reached the bottleneck created by the encroaching marsh, the right of their formation was in the surf. The men struggled to maintain their positions in the lines as they pressed on toward the waiting enemy.

When the Federal assault force started forward, the Union land batteries fell silent. The naval bombardment gradually slackened. Confederate sentries warily peeked over the parapet and saw the mass of soldiers moving toward the fort. General Taliaferro gave the order for the garrison to man their positions.

The 51st North Carolina rushed out of the bombproof. Led by Colonel McKethan, the men ran to their assigned areas, ecstatic to be free of the close confines of the bombproof. They, too, forgot their hunger and fatigue as they crowded behind the parapet atop the curtain. From the rampart, the soldiers could see the approaching enemy in the fading light. Each man was handed a cartridge box with forty rounds of ammunition.17

The Union infantry was squeezing out of the narrow gap between the marsh and the ocean, roughly 200 yards from Wagner. They were moving quickly. There were four gun emplacements in the curtain, but the artillery pieces had been dismounted earlier in the day to protect them from the Union bombardment. The Union troops’ quick approach left no time to remount the guns. The North Carolinians would have to defend their position by musketry alone.

Gun crews hurriedly rolled a section of howitzers through the new sally port. They began setting up their two guns in front of the southwest corner of the fort, below and to the right of the 51st North Carolina. Along the top of the wall, to the right of the 51st Regiment, three companies of the Charleston Battalion were in position. The rampart to the left was strangely empty. The men of the Fifty-First steeled themselves for the assault.

As the 54th Massachusetts began emerging from the bottleneck, the regiment turned toward Battery Wagner’s curtain. Suddenly, Confederate artillery at Fort Sumter and Battery Gregg opened up on the formation with shot and shell. Cannon fire from Wagner’s bastions erupted, and the two field pieces joined in with double canister. The artillery fire caused the regiment to pause. Then, with a loud “Hurrah,” the Union troops rushed forward toward the Confederate works.

The North Carolina men at the parapet watched the enemy stumble along the beach and then turn toward the fort. Confederate artillery knocked large holes in the enemy formation, which paused, shouted, and then charged. The Confederates, standing two rows deep on the rampart, replied with a Rebel yell and aimed their muskets at the fast-approaching Yankees. When the 54th Massachusetts was 150 yards from Wagner’s walls, General Taliaferro gave the order to fire.

The Yankees running toward the fort held their formation as best they could. Some stumbled and tripped in the numerous shell holes left by the earlier bombardment. Others tripped over fallen comrades. It was almost totally dark by then, and the Union men used the muzzle flashes of Confederate cannon to guide them toward the fort. As the mass of infantry closed on the fort, “a sheet of flame, followed by a running fire, like electric sparks”18 ran the length of the parapet. Dozens of the Massachusetts men fell. The attackers now realized that the preparatory bombardment had not accomplished its job. Battery Wagner’s defenses were intact, but the Yankee soldiers had no choice but to continue rushing toward the fort.

The Massachusetts men pressed forward. The regiment paused and split into two pieces when it hit the moat in front of the wall. Parts of the moat had been filled by sand thrown up during the artillery barrage preceding the assault. The Union infantry were able to cross these sections of the ditch easily, while other soldiers of the regiment had to wade through waist-deep water. The first men to cross the moat began pulling out the sharpened palmetto stakes protruding from the bottom of the wall as the rest of the regiment struggled to reach the base of the curtain.

Inside the fort, the far-right gun was manned by the 22nd Georgia Artillery. As the Yankee infantry advanced, the Georgians fired their thirty-two-pound howitzer twice. The recoil from the second shot pushed the gun off its platform. The crew suddenly found themselves with no piece to man.

To the left of the Georgians, there were two embrasures on the bastion wall where the wall bent and faced southeast. The nearer opening had a working gun, but the embrasure had been filled during the Union bombardment. The next embrasure was open, but the gun at that position was disabled.

The corporal in charge of the gun crew grabbed some men from the 51st North Carolina, and with their help, they moved the working gun from the first embrasure to the second. From that position, the gunners could aim down the attackers’ left flank as they crossed the ditch. They fired eight loads of canister into the Union mass “and caused terrible havoc.”19

The 51st Regiment saw the Union confusion at the ditch. They fired another volley into the milling throng as Colonel Shaw was reforming his regiment’s lines at the base of the wall. The troops close to the wall were partially shielded from the fusillade. The Union soldiers on the opposite side of the moat took the brunt of the North Carolinian’s volley and fell back. The two Confederate howitzers fired canister into the withdrawing group’s flank, and the Yankee soldiers “ran like a crowd of maniacs.”20

The fleeing Union soldiers forced themselves through the regiments following the 54th Massachusetts. The routing men broke the alignment of the 6th Connecticut and 48th New York, disrupting and delaying the two regiments as they were passing though the defile made by the marsh. Both regiments had to halt and realign their formations before continuing toward the fort.

Colonel Shaw rallied his remaining troops, a little over half his regiment, and charged up the wall. He jumped on top of the parapet, started waving his sword above his head, and shouted, “Forward, Fifty-Fourth!” The colonel was immediately shot and bayoneted. He died where he fell. The Union men following their gallant commander were able to storm over the parapet where brutal hand-to-hand fighting ensued. The frantic defenders fought with bayonets, swords, and knives. Some of the Union attackers were drug into the fort and clubbed to death. The fighting on top of the rampart only lasted a few minutes before the Massachusetts men were forced out of the fort and back onto the outside wall.

The sloped walls of Battery Wagner provided some protection for the 54th Massachusetts. Cannon inside the fort could not be depressed sufficiently to fire on the Union soldiers. The soldiers could now use their muskets to fire at the Confederates who leaned over the parapet to shoot at them. But the Union men were caught in a crossfire between the Charleston Battalion and the 51st North Carolina. In addition, the Tar Heel soldiers began rolling hand grenades and lit shells down the wall into the massed Union troops.

Realizing that no support was coming from the rest of the brigade, the men of the Fifty-Fourth began to retreat. When they descended the wall and re-crossed the moat, they were once again subjected to a murderous fire from the defenders inside the fort. The regiment broke and ran,* this time crashing into the 76th Pennsylvania and 9th Maine as those two regiments were squeezing through the bottleneck on the beach. Both units were thrown into complete disarray, with some of their soldiers joining the Massachusetts men in their panic-stricken flight.

Fifteen minutes after the 54th Massachusetts had been mauled, the 6th Connecticut struck Battery Wagner to the right of the curtain. They were able to gain the top of the rampart on the southeast corner of the fort. The 31st North Carolina had failed to man this bastion,** and the Connecticut men scrambled into the fort in the area between the wall and the bombproof. The 48th New York, advancing behind the Connecticut men, assailed the fort farther to the right, from the southeast corner along the sea face. Part of the regiment was able to get into the bastion next to the Connecticut troops.

The remaining three regiments of Strong’s brigade had been completely disrupted by the waves of fleeing Massachusetts men. When they finally got organized and started toward the fort, they were met by heavy fire. The 51st Regiment assisted the South Carolina artillerists in remounting and firing the guns in the curtain. These cannon, in addition to the field howitzers at the southwest corner of Battery Wagner, mowed down the advancing regiments with canister. At the same time, the Charleston Battalion and the 51st Regiment fired volley after volley into the flanks of the advancing ranks. One South Carolina major observed, “Few could move within that fatal area and live.”21

The three Union regiments, taking fearful losses, were unable to reach the walls of the fort and hastily withdrew. At this point, General Strong, who had been mortally wounded, gave orders for the entire brigade to retreat. The withdrawal left the men of the 6th Connecticut and 48th New York isolated inside the fort.

When General Seymour saw Strong’s attack crumbling, he ordered up Putnam’s Brigade. Much to his horror, Putnam refused to move his troops, saying that General Gillmore had ordered him to remain in place. A half hour passed before Putnam finally moved his brigade forward. Putnam and some of his men survived the furious fire coming from the Charleston Battalion and 51st North Carolina and forced themselves into the bastion where the 48th New York and 6th Connecticut continued to fight.

By this time, about 300 Yankees were in the bastion and on top of the bombproof. In addition to Strong’s New York and Connecticut men, Colonel Putnam had led fragments of the 7th New Hampshire and the 62nd and 67th Ohio Regiments into Battery Wagner. Putnam’s trailing regiment, the 100th New York, halted outside the walls. In the darkness, the New Yorkers mistook their fellow soldiers for Confederate infantry and fired into the Union troops on top of the ramparts. The 100th New York then retreated without attempting to climb into the fort.

General Taliaferro directed the 51st North Carolina to fire at any Union soldiers who tried to exit the bastion. He then asked for a volunteer to lead an assault against the Yankee infantry. Major McDonald of the 51st Regiment and Captain W. H. Ryan of the Charleston Battalion immediately volunteered. Taliaferro chose Captain Ryan, who organized a group to attack the Union troops. Ryan was killed almost as soon as the counterattack began. The Rebels fell back.

A second attempt was made to dislodge the Yankees from the salient. Major David Ramsey, also of the Charleston Battalion, led another group of men toward the bastion. Ramsey was struck by a bullet before his men could close with the Yankee infantry. After Ramsey fell dead, the second attempt to drive the Union troops from the battery fell apart.

Putnam immediately called for support to take advantage of his position inside the fort. Seymour, who had been wounded during the Second Brigade’s assault, sent orders for Stevenson’s brigade to come to Putnam’s aid. However, upon learning that Colonel Seymour was wounded, General Gillmore replaced the assault commander with Colonel John Turner. The change in command created a great deal of confusion, and Stevenson’s brigade never moved forward.

The soldiers trapped in the southeast bastion waited an hour for support. While they were holding on, a Confederate Minié ball blew off the back of Colonel Putnam’s head. Command of the Yankee troops devolved to Major Lewis Butler of the 67th Ohio, the only field officer left standing in the bastion. Butler, his men running low on ammunition, ordered the soldiers to withdraw. When Lieutenant Barret of the 48th New York retreated, the bastion where the regiment had fought for the past three hours “was literally filled with dead and wounded, piled up even with the parapet.”22 About 100 Union soldiers were unable or unwilling to escape and remained inside the fort.

As Butler was withdrawing his men from the fort, a contingent of the 32nd Georgia arrived from James Island. These men moved onto the sea face wall and advanced along the rampart to the top of the magazine. From this position, they were behind the Union troops. Now completely surrounded, the survivors in the fort surrendered.

By eleven o’clock, all was quiet. The men of Battery Wagner had managed to hold onto their fort after repelling three assaults. The Federal infantry straggled back to their lines in the dark.

The next morning revealed the extent of carnage the Union troops suffered during the previous night’s assault. The southeast bastion and the moat were full of Union dead, piled three high in some places. The ground in front of the fort was littered with mangled bodies. Fort Wagner’s garrison spent that Sunday burying blue-coated corpses in a mass grave near the beach. The Confederate wounded and the Union prisoners were transported to Charleston.

Union forces lost an estimated 1,500 men killed, wounded, or captured, during the three charges on Battery Wagner. The casualties included 111 officers.23 The Confederates lost 174 men.24 Of the 174 Confederate casualties, the 51st Regiment’s official losses were sixteen killed, fifty-two wounded and six missing.25 The regiment’s service records indicate fifteen killed, fifty-six wounded (seven of these would die from their wounds), and none missing. All the missing men listed in the official count were present the next month, and one of the men listed as killed, Private William Brewer of Company F, not only survived the battle, but he also survived the war.

During the Union bombardment of Battery Wagner, Private Uriah Bass, Company I, 51st North Carolina was struck by a shell fragment. The fragment hit him in the top of head, splitting the private’s head open. He was transmitted to Trapman Street Hospital the next day, where doctors sewed Bass’ head back together. Private Bass was back on duty within a month of being wounded.

When the 54th Massachusetts assailed the fort, Corporal Samuel Spivey of Company F was standing shoulder-to-shoulder with his son, Aiken, a private in the same company. Samuel was killed during the battle. His son was wounded in the head and died five weeks later.

After the battle, General Taliaferro noted that the 51st North Carolina was among the units who demonstrated “efficiency and gallantry” during the Union assault. In his report of the battle, the general wrote:

Colonel McKethan’s regiment, Fifty-first North Carolina troops, redeemed the reputation of the Thirty-first regiment. They gallantly sought their position under a heavy shelling, and maintained it during the action. Colonel McKethan, Lieutenant-Colonel Hobson and Major McDonald are the field officers of this regiment and deserve special mention.26

Private James Douglas of Company F was not as upbeat as General Taliaferro about the bloody battle for Battery Wagner. In a letter home a week after the battle, the nineteen-year-old private told his mother:

I have been in a big fight on Morris Island on the 18 of this month. I came out safe and sound but there was 6 of our men got killed—S. Clemons, S. Spivy, W. Boon, A.C. Baxley, S. Lock, and Jepsy Henderson. I should like to go home very much at this time. I want to see you all worse than I ever did in my life. We will have to go back to that island again. I expect it.27

Aftermath of the Assault

After the slaughter on the 18th of July, General Gillmore determined that another direct assault on Battery Wagner would be too costly. He decided to capture the stronghold through siege operations. His sappers began digging zigzag trenches, moving ever nearer to the fort. As the siege progressed, Gillmore moved his infantry and artillery closer and closer to Wagner. By September 6, the sap had reached Battery Wagner’s moat. General Gillmore ordered an assault for the next morning. During the night, the Confederate garrison slipped away, leaving an empty fort for the enemy.

*Captain Luis Emilio of the 54th Massachusetts stated that the regiment made an orderly withdrawal. In his account of the assault, Emilio never mentions the soldiers running.

**After the fight, General Taliaferro stated that the 31st North Carolina had refused to leave the bomb-proof and take their assigned position in the bastion. General Beauregard stated that the regiment had abandoned their position. Lt. Col. Charles Knight, commanding the 31st Regiment at the time of the assault, reported that one of the cannon in the bastion had been dismounted by the Union bombardment. This “busted gun” obstructed the way to the rampart and prevented his men from taking their positions in the southeast bastion.

Notes

1Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 345.

2Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 541.

3Robert Cogdell Gilchrist, The Confederate Defence of Morris Island, Charleston Harbor: by the Troops of South Carolina, Georgia, And North Carolina, In the Late War Between the States (Charleston: The News and Courier Book Presses, 1884) 8.

4Walter Clark, ed., Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65, 5 vols. (Goldsboro: Nash Bros., 1901) 3: 207; Gilchrist, 8 & 9.

5Gilchrist, 9.

6Gilchrist, 8 & 9.

7Gilchrist, 9.

8Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 523.

9Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 572.

10Histories, 3: 207 and Gilchrist, 20.

11Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 2): 207-210.

12This account of the assault on Battery Wagner was compiled from multiple sources: Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 74-77, 345-372, 413-419, 524-572; Histories, 2: 514, 3: 206-210, 5: 161-167; Johnson, 100-107; Gilchrist, 18-22; Wilmington Journal 23 Jul. 1863; Emilio, 43-57; and North Carolina Troops, 12: 261-264.

13Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 267.

14Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 75.

15Fayetteville Observer 23 Jul. 1863.

16Colonel Hector McKethan, letter to Captain Edward White, 29 Sep. 1863, Thomas L. Clingman Papers, Southern Historical Collection, UNC, Chapel Hill.

17Fayetteville Observer 23 Jul. 1863.

18Luis F. Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment (1891) (Arcadia Press, 2017) 47.

19Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 570.

20John Johnson, The Defense of Charleston Harbor: Including Fort Sumter And the Adjacent Islands, 1863-1865 (Charleston: Walker, Evans & Cogswell Co., 1890) 104.

21Gilchrist, 22.

22James M. Nichols, Perry’s Saints (Boston: D. Lothrop & Co., 1886) 170.

23Emilio, 50.

24Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 373.

25Wilmington Journal 23 Jul. 1863.

26 Official Records, Series 1, 28 (part 1): 419.

27James Ervin Douglas, letter to Eleanor Branch, 26 Jul. 1863.

Map of Charleston Harbor: Henry Davenport Northrop, Life and Deeds of General Sherman (Boston: Gately & O’Gorman, 1891) 457.

Drawing of Battery Wagner: Official Records Atlas, Plate 69

Drawing of Confederate Torpedo: Gillmore, 236.

Drawing of 54th Massachusetts Charge: History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865

Copyright © 2021 – 2024 by Kirk Ward. All rights reserved.