NOTE: During 1865, the 51st North Carolina was assigned to Clingman’s Brigade (commanded by Col. William Devane) of Hoke’s Division. Few records exist for the regiment for 1865.

Background

Shortly after the fall of Fort Fisher, Grant assigned Brigadier General John Schofield to command the Union Department of North Carolina. With Wilmington secure, Schofield was ordered to move on Goldsboro and establish a rail link between that town and Wilmington. Schofield would wait at Goldsboro for General William T. Sherman, whose army was heading for the North Carolina border after laying waste to much of South Carolina. Sherman would resupply at Goldsboro, and reinforced by Schofield’s forces, continue his rampage in North Carolina.

Schofield began planning the march on Goldsboro. He quickly discovered that Wilmington did not have enough rolling stock and wagons to support the expedition, forcing General Schofield to move his base of operations to New Bern.[i] On March 6, a provisional corps of three Union divisions under the command of Major General Jacob Cox left New Bern, bound for Goldsboro.

The Confederacy was assembling a hodgepodge army to stop Sherman. On February 22, the day Wilmington fell, President Jefferson Davis appointed General Joseph Johnston to command all armies east of the Mississippi and outside of Virginia. These forces included the old Army of Tennessee, 4,500 men under the command of Lieutenant General Alexander Stewart, a ragtag group of 5,400 soldiers under Lieutenant General William Hardee, who had opposed Sherman’s march since he left Atlanta, Bragg’s “corps” of 5,500 men, which consisted of Hoke’s division and a contingent of Junior Reserves (made up of seventeen-year-old boys), and Wade Hampton’s and Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry commands.[ii]

The Opponents Arrive

Johnston ordered General Bragg to delay the Federal expedition approaching from New Bern. Bragg moved his corps to Kinston by rail. Second Lieutenant Augustus McKethan was commanding Company B of the 51st Regiment during the move to Kinston. Because most of the men in the company were from Duplin County, McKethan was ordered to keep his men in sealed boxcars so they would not leave the train and head for home. During the first water stop, Lieutenant McKethan discovered two soldiers by the side of the track. One said he could see his house from where they were standing. McKethan allowed the men to leave after they promised to rejoin the company the next day. Other men quickly followed. By the time the train reached Kinston, only McKethan and Company B’s First Sergeant remained. True to their word, the absent men all rejoined the company the next evening.[iii]

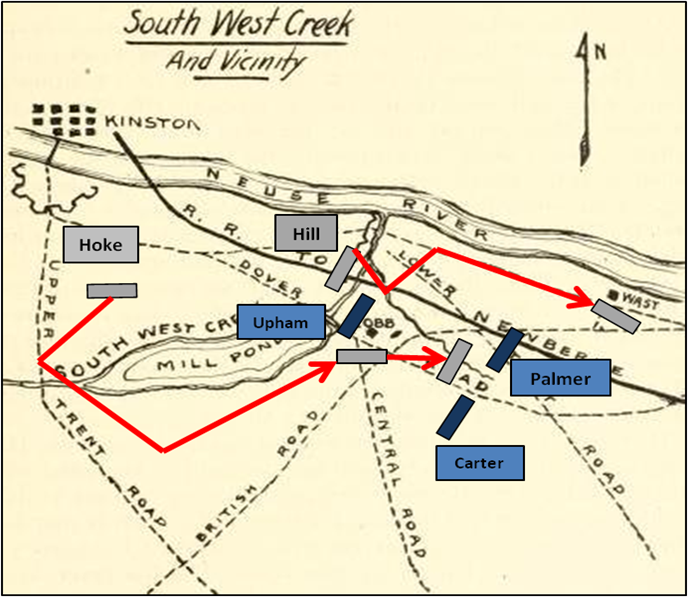

From Kinston, Bragg’s troops marched across the Neuse River to Southwest Creek, a few miles southeast of the town. Hoke’s division began constructing earthworks on the west bank of the stream. On March 7, two of Cox’s divisions, one commanded by Brigadier General Innis Palmer and the other commanded by Brigadier General Samuel Carter, approached the creek. General Cox deployed his divisions a couple of miles from the Confederates, with Palmer on the right guarding the railroad and Carter a mile to the south, astride the Dover Road. Carter sent Colonel Charles Upham’s small brigade (about 1,000 soldiers) forward to hold the point where the Dover Road crossed Southwest Creek.[iv]

During the night, General D. H. Hill arrived with Confederate reinforcements, including the North Carolina Junior Reserves, three regiments of seventeen-year-old boys. Early the next morning, General Hoke pulled his division out of the line along the creek and moved to the right. Hill slid his troops into the works vacated by Hoke’s men.

The Battle of Southwest Creek

Hoke’s division circled a large millpond on the right and approached Upham’s brigade from the south. Scouts warned Colonel Upham of the approaching Confederates, and he sent the 27th Massachusetts to intercept Hoke’s troops along the British Road. Hoke’s men attacked the Massachusetts regiment and pushed it back toward Southwest Creek.

When D. H. Hill heard gunfire from the south, he moved against Upham’s right flank. The Junior Reserves moved out quickly at first, but then one of the regiments routed. The boys in the other two regiments lay down and refused to advance. General Hill left the Reserves where they lay and sent his veterans forward. The Rebel infantry struck the 15th Connecticut’s flank, and “the Yankees ran in the wildest confusion,” retreating toward Hoke’s advancing troops.[vi]

As Hill and Hoke were about to capture Colonel Upham’s entire brigade, General Bragg intervened. Bragg mistakenly believed that Hoke was routing all of General Cox’s command. In a typical blunder, Bragg ordered Hill to break off his advance and move to the northeast. General Hill rushed his force several miles up the Neuse Road to its intersection with the British Road. There, Hill’s division waited to intercept the Yankees that Bragg assumed would flee from Hoke’s advance.

D. H. Hill’s withdrawal from the fight took the pressure off the Union right flank, allowing part of Upham’s brigade to escape. General Hoke, now without support, halted to gather up his 800 prisoners[vii] and send them to the rear. After disposing of the captured Yankees, Hoke reformed his division and headed east, looking for the rest of Cox’s corps.

Hoke’s delay gave General Cox’s two divisions time to hastily throw up earthworks. In addition, Cox’s third division arrived on the field and went into line between Palmer’s and Carter’s divisions. When Hoke’s Confederates finally reached the Union positions, they paused. After the Federals repelled a few probing attacks, the Rebels withdrew to Southwest Creek. D. H. Hill’s men did not encounter any fleeing Yankees along the British Road, and at the end of the day, they returned to their trenches.[viii]

That night, the Federals dug in while waiting for more reinforcements marching up from Wilmington. Early in the morning, Hoke moved his division around the Confederate left, hoping to surprise the Yankees again. At dawn, Hoke’s infantry probed the Union flank and decided that the position was too strong to assault. The two sides sat in their entrenchments the rest of the day.

On the morning of March 10, General Bragg ordered an all-out attack on the Federal defenses. Before dawn, Hoke’s division again maneuvered around the Union left flank. As the sun rose, General Hoke’s men slammed into the Yankee troops. When General Hill heard Hoke’s men firing, he ordered his division forward. Hill’s soldiers quickly overran a section of Yankee trenches, but they had to halt to reform their lines. Before General Hill could resume the assault on the Union front, Hoke’s division ran into a large body of Union infantry concentrated behind well-constructed breastworks. Hoke broke off the attack. When Hill heard that Hoke had halted, he ordered his men back to the Confederate lines.[ix] The Battle of Southwest Creek was over.

General Bragg pulled his troops back across the Neuse River. After spending the night near Kinston, Hoke’s division made a leisurely five-day march to Smithfield.[x] Although Bragg’s failure to turn back the Yankees was disappointing, it was not unexpected. Bragg’s small force had accomplished its primary objective of buying Johnston time to organize a defense against Sherman’s approaching army.

[i] John G. Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1963) 285.

[ii] Weymouth T. Jordan, Jr., The Battle of Bentonville (Wilmington: Broadfoot Publishing, 1995) 7-8.

[iii] Walter Clark, ed., Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65, 5 vols. (Goldsboro: Nash Bros., 1901) 3: 216.

[iv] Official Records, Series 1, 47 (part 1): 912.

[v} Johnson Hagood, Memoirs of the War of Secession (Columbia: State Company, 1910) 353.

[vi] Official Records, Series 1, 47 (part 1): 1087.

[vii] Official Records, Series 1, 47 (part 1): 62.

[viii] Official Records, Series 1, 47 (part 1): 977 and Hagood, 354.

[ix] Barrett, 290.

[x] Daniel W. Barefoot, General Robert F. Hoke: Lee’s Modest Warrior (Winston-Salem: John F. Blair, 1996) 291-292.

Copyright © 2021 – 2024 by Kirk Ward. All rights reserved.