Background

At midnight on May 30, 1864, the stage was set for a bloody battle between the North and the South. Union General Ulysses Grant had once again maneuvered around Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Grant felt that he was finally in a position to destroy Lee’s army. The next few days could end the war.

The situation was ominous. Fitzhugh Lee’s Confederate cavalry division was guarding the crossroads at Old Cold Harbor. A Yankee cavalry division was just a few miles away, preparing to move against the Rebel troopers. A Union corps was on its way to Cold Harbor from the north, and Grant was starting to shift the left of his army to the same spot. General Robert Hoke’s division was preparing to reinforce Lee at Cold Harbor. With all these forces converging, something big was bound to happen.

Cold Harbor, First Day

At 5:15 in the morning on May 31, the 51st North Carolina, accompanied by the 8th and 31st North Carolina Regiments, boarded a train in Petersburg. By early afternoon, the regiments were a few miles from Cold Harbor. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry division was stationed at the crossroads. As Union cavalry approached, Fitz Lee requested that Clingman’s troops be sent to support the Southern horsemen.[i]

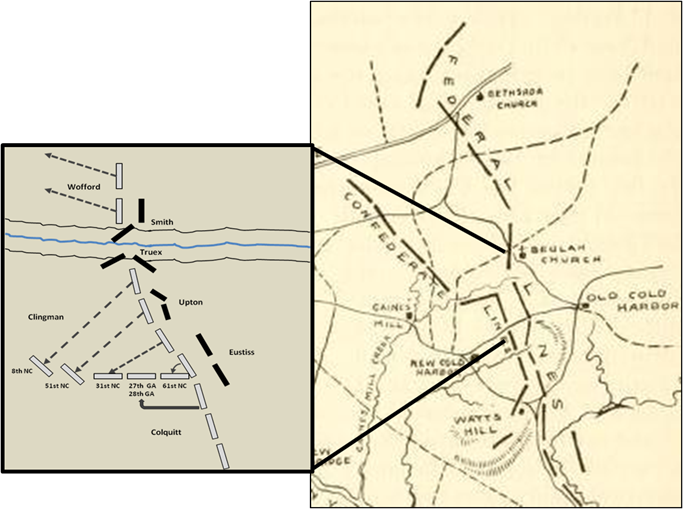

When the 51st Regiment reached the crossroads, Fitz Lee’s Confederates were already engaged with Union cavalry. The men of the Fifty-First went straight into action. General Clingman’s infantry formed to the left of the Rebel troopers, with the 31st Regiment next to the cavalry, then the 8th Regiment, and then the 51st Regiment on the far left.

Shortly after the brigade formed its lines, General Hoke ordered Clingman to move the 51st North Carolina forward 400 yards to support a group of dismounted Rebel cavalry. Clingman led the regiment forward and positioned the soldiers to the right of the Confederate troopers. The 51st North Carolina was now in the “most dangerous and exposed” part of the line. The Tar Heels were subjected to heavy artillery and rifle fire but suffered few casualties.[ii]

The Yankee cavalry made several charges against Clingman’s line but were repulsed each time. Trying a new tactic, three of the Union regiments slipped around the Confederate left and launched a flank attack.[iii] The rush of enemy cavalry on the flank surprised the Rebel defenders. Soon, a detachment of Confederate cavalry to the 51st Regiment’s left, running low on ammunition, withdrew. The troopers’ unexpected retreat exposed the Fifty-First’s flank.

General Clingman sent two of the 51st Regiment’s companies 150 yards to the left to counter the Union threat from the flank. Not long after, the Rebel cavalry on the right gave way, retreating in squads. Clingman, now with both flanks exposed, feared his brigade would be surrounded. He ordered his regiments to withdraw a few hundred yards.

As the brigade pulled back, Union cavalry got between the 51st and 8th Regiments. At the same time, Yankee troopers struck the Fifty-First’s left flank. Being attacked from three sides, the 51st Regiment’s orderly withdrawal turned into a hasty retreat. In the confusion of the retreat, the regiment suffered thirty-seven men killed and wounded and nine soldiers captured.

While the brigade was occupying its new line, a shell fragment hit General Clingman in the head, tearing away the front of the general’s hat and stunning him briefly. Despite his wound, Clingman managed to get his regiments positioned on the edge of a field, about three hundred yards behind their former position.[iv] After realigning the brigade and allowing the 51st Regiment to catch its breath, Clingman withdrew his brigade to a low ridge about a half mile to the west.

Fitz Lee’s cavalry joined Clingman’s infantry on the ridge. The infantry and cavalry formed new lines and began hastily entrenching using hands, bayonets, tin plates, and anything else that could scrape out a hole.[v] But the Union cavalry had halted its attack. The Confederates spent the night in place without seeing any more action.[vi]

Digging In

After dark, General Clingman’s fourth regiment, the 61st North Carolina, joined the rest of the brigade. Clingman deployed his North Carolinians with the Sixty-First on the far right, the Thirty-First to the left of the Sixty-First, the Fifty-First to the left of the Thirty-First, and the Eighth anchoring the brigade’s left. The left flank of the 8th North Carolina rested on the edge of a ravine with a small stream running through it. The floor of the ravine was swampy and thickly wooded.

During the night, the rest of General Hoke’s division arrived. Hoke positioned General Alfred Colquitt’s brigade to Clingman’s right, then aligned General James Martin’s brigade to Colquitt’s right. Hagood’s brigade, the last to arrive, was placed in reserve. Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee ordered Major General Richard Anderson to move his corps to Cold Harbor in support of Hoke’s division.

Major General Philip Sheridan, overall commander of the Union cavalry, notified General Meade that more Confederate infantry was arriving in the Cold Harbor area. He warned Meade that the Union cavalry would not be able to hold the road junction at Cold Harbor without reinforcements. Meade responded at once, ordering Horatio Wright’s VI Corps to march from the far right of the Union line to Cold Harbor, on the far left. Baldy Smith’s XVIII Corps was ordered to fill the gap between Wright’s corps and the rest of the Union line.[vii]

Cold Harbor, Day 2

By morning, General Joseph Kershaw’s division, on the right of Anderson’s corps, was on the field with Hoke. Without delay, Kershaw attacked the Union cavalry at the Old Cold Harbor crossroads. The attack was quickly repulsed. General Hoke was supposed to support Kershaw’s advance, but the assault was repelled before Hoke’s men could join the fray.[viii]

Thinking a large body of Union infantry was already at Cold Harbor, the Rebels steeled themselves for the inevitable counterattack. Kershaw deployed his division in line, with Brigadier General William Wofford’s brigade of Georgians on the division’s far right. Wofford’s brigade was to the left of the 8th North Carolina, with its right flank resting on the opposite side of the ravine. This arrangement left a seventy-five-yard gap between Wofford’s position and Clingman’s brigade.

Clingman was concerned about the gap on his left and pointed it out to General Hoke. Hoke then positioned Hagood’s brigade forward and to the left of Clingman to cover the gap. However, around three o’clock in the afternoon, Hoke shifted Hagood’s brigade to the far right of the line, leaving Clingman’s left flank unprotected. General Clingman was unaware of Hagood’s move.[ix]

Not long after Hagood’s brigade moved, the Union artillery opened fire. A heavy bombardment continued until 4:30 in the afternoon. As soon as the artillery fire ceased, the two Federal corps advanced on the Confederate works.[x] The Union troops attacked all along Hoke’s and Kershaw’s fronts.

The Rebel line ran roughly south to north. Hoke’s division manned the right of the Confederate defenses. Kershaw’s division, to the left of Hoke, continued the line northward. Clingman’s brigade anchored the northern end of Hoke’s line. To Clingman’s left, Wofford’s South Carolinians anchored the southern end of Kershaw’s line. Neither brigade commander was aware that the seventy-five-yard gap between them was open to the advancing Yankees.

Two divisions (six brigades) of VI Corps attacked Hoke’s lines. Another two divisions (six brigades) of XVIII Corps assailed Anderson’s defenses. The twelve Union brigades numbered approximately 20,000 men. Anderson and Hoke had about 10,000 soldiers between them, but their troops were dug in.[xi]

Three of VI Corps’ brigades advanced across open ground toward the southern end of Hoke’s position. None of these troops got close to the Confederate works. As they neared the Rebel lines, they were driven back or pinned down by a storm of canister and musket balls.[xii]

Wright’s remaining three brigades fared better on the northern end of Hoke’s line. While the Federal attack was being pressed in Clingman’s front, General Emory Upton’s brigade approached the North Carolinians’ entrenchments at an angle from the north. Formed in four lines, the brigade entered a shallow depression slightly to the left of the 51st North Carolina’s lines. This movement went unobserved by the Confederates, who were concentrating on repelling the lines of infantry coming directly at them.

The first three ranks of Upton’s formation were filled by the Second Connecticut Heavy Artillery. This regiment had been pressed into service as infantry just two weeks before. As General Grant fed more and more men into the meat grinder of the Overland Campaign, he quickly realized he would need replacements. Since Washington was under no immediate threat, he ordered the heavy artillery units in the capital’s defenses to grab rifles and report to the Army of the Potomac. The Connecticut men were among the units ordered into the field.

The artillery units were overmanned compared to infantry regiments. The Second Connecticut had roughly 1,800 soldiers, almost twice the number of a standard infantry regiment. After three weeks of constant bleeding, Upton’s other regiments were not close to full strength. Three of the brigade’s veteran regiments, battered and depleted, filled the fourth rank of the advancing formation.[xiii]

Hidden from the Rebels’ view, Upton’s men crept toward the section of the Confederate trenches manned by the 51st North Carolina. When they were about twenty-five yards from the Confederate position, they ran into a barrier made of felled pine trees. The Rebels had left two gaps in the barrier, a few yards apart. Four men at a time could squeeze through one of the gaps. The Yankees slipped through the openings and approached the Rebel trenches.[xiv]

General Clingman’s brigade was taking a break between Union assaults. Suddenly, the Connecticut men appeared “within eight or ten paces” on the left of the 51st Regiment. Clingman shouted, “Aim low and aim well!” [xv] The entire brigade fired a volley into the Yankee mass, cutting down the front ranks. After several volleys from the Tar Heel infantry, the attackers all lay down. The Confederates began firing into the mass on the ground until they could not tell the living soldiers from the dead. The Rebel infantry stopped shooting, and when they did, the surviving Yankees jumped up and ran. The brigade resumed firing, killing or wounding many of the fleeing men.[xvi]

Colonel William Truex’s brigade was advancing to the right of Upton’s brigade. Part of Truex’s line stumbled into the ravine running between Wofford’s brigade and the 8th North Carolina. Wofford’s rightmost regiment, which had been entrenched at the edge of the ravine, fired one volley at the advancing Union lines and fled the field. With Wofford’s men gone, the gully now provided a safe refuge from Confederate fire.

To the north of Truex, Colonel Benjamin Smith’s brigade was being pummeled by Wofford’s remaining regiments. Smith’s men, seeking shelter from the deadly Confederate fire, veered left and joined Truex’s brigade in the ravine. Inside the ravine, the Union regiments got scattered and mixed. Some men were wading in waist-deep water, while others were slogging along in knee-deep mud. The troops started looking for a path up the banks of the gully, and soon men were climbing out on both sides of the ravine.[xvii]

As Union infantry emerged from the thick woods along the southern edge of the ravine, they ran smack into the 8th North Carolina. The North Carolinians fired a volley, and the Yankees faded back into the trees. The 8th Regiment bent its line to the left to face this new attack while they continued to fend off Truex’s other troops assaulting their front.

More Yankee infantry continued climbing out of the ravine and rushing the 8th North Carolina’s line. The attack spilled around the rear of the regiment. Soon the 51st North Carolina found itself in the same predicament as its fellow regiment. With the two North Carolina regiments almost completely surrounded, the Union troops started demanding the Confederates surrender.

Some of the Rebel soldiers dropped their weapons and gave up. Others continued to fire at their attackers. Captain John Patterson of the 14th New Jersey rushed Major McDonald of the 51st North Carolina, drew his pistol and aimed it at McDonald’s head. He told McDonald to order his men to cease fire. McDonald did as he was told, and the Yankees snared 166 prisoners.[xix]

As the 8th and 51st Regiments fought for their lives, the action died down in the rest of the brigade’s front. Clingman, whose entire staff had been killed or wounded, directed the 31st Regiment to swing to its left and form a new line facing the Union flank attack. The 8th and 51st Regiments made a fighting withdrawal and moved into the new line formed by the 31st Regiment. With half his hat brim missing and brandishing a piece of fence rail as his only weapon, Clingman organized a counterattack. The Confederates retook their trenches, but only momentarily. The Yankees mounted their own counterattack and drove the North Carolinians back again.

Clingman reformed his line and added the 61st Regiment to his next attack. In addition, the 27th and 28th Georgia Regiments, of Colquitt’s brigade, came over from the right to give Clingman’s brigade a hand. The reinforced brigade charged the Yankees again. They recaptured most of the brigade’s original lines. The Rebels doggedly held their recaptured works until they could construct new earthworks a short distance to the rear.[xx]

The Second Connecticut Artillery had been driven off by Clingman’s men, but they had not left the field. They had pulled back into the depression that had masked their advance. Some Confederate prisoners, one of whom was Major McDonald, passed General Upton on their way to the Yankee rear. McDonald told Upton that the 51st Regiment’s flank had been turned.

Upton got the Connecticut men moving and occupied the trenches that had just been overrun by Truex’s flank attack. They moved down the trenches to the spot of their earlier advance and held that position for the next thirty-six hours.[xxi]

While Truex’s brigade was driving Clingman’s men back, Smith’s regiments climbed from the ravine on the opposite side. They immediately attacked Wofford’s exposed flank. Wofford’s Georgians were already desperately fending off two Yankee brigades assaulting their front. The sudden appearance of enemy infantry on their flank and rear proved too much for the Georgians. Wofford’s entire brigade broke and ran.

The three Union brigades pushed northwards and struck the flank of Brigadier General Goode Bryan’s brigade. Bryan’s men began speedily following Wofford’s regiments toward the rear. The soldiers on the northern part of Bryan’s line were able to bend to the right and finally stop the Yankee advance. The Union attack paused. There was now a half-mile gap in the Confederate lines between Hoke’s division and Kershaw’s lines.[xxii]

Colonel John Henagan’s brigade, immediately to the north of Goode Bryan, had easily repulsed the Yankee assault on its front. Kershaw pulled two regiments from Henagan’s line and sent them, with several pieces of artillery, to drive the Federals out of the captured works. The Union infantry, having fought a two-hour running battle, were exhausted. They hastily withdrew when the Confederate’s counterattacked.[xxiii]

Several miles to the north, the rest of Robert E. Lee’s army occupied a five-mile-long defensive line. The Second Corps, under Jubal Early and the Third Corps, commanded by A. P. Hill, along with John C. Breckinridge’s unattached division, sat behind their works and waited. Opposing the Confederates were the Union II, V, and IX corps under Generals Hancock, Warren and Burnside, respectively. At seven o’clock in the evening, two of Early’s divisions launched an attack into the center of the Union lines. The attack made good progress at first, but the Federals were able to organize a stiff resistance and drove the Confederates back to their lines.

Cold Harbor, Day 3

General Grant’s belief that the Army of Northern Virginia had lost its fighting edge was buttressed by the Union army’s progress during the day’s battle. He felt that an all-out attack on the Confederates near Cold Harbor the next day would finally finish off Lee’s army. Meade agreed and issued orders for a dawn assault. During the night, Hancock’s II Corps began shifting southward to support the attack. General Lee, in response, sent Breckinridge’s division and two divisions of A. P. Hill’s corps to reinforce the southern end of Confederate line.

Hancock’s lead brigade did not reach its new position until after dawn. The rest of the corps trickled in over the next few hours. Meade postponed the attack until five o’clock in the afternoon. Hancock struggled to get his corps into position in time for the rescheduled attack. While II Corps was muddling about, a torrential rain fell, turning the field in front of the Federals to mud. Meade decided to postpone the attack again, to 4:30 the next morning.

While General Lee was shifting troops southward, General Richard Anderson was realigning the Confederate defenses around Cold Harbor. He restored the lines abandoned by Wofford’s brigade and plugged the gap between Kershaw’s and Hoke’s divisions. Clingman’s brigade, which suffered more than half the division’s casualties that day, was placed in reserve. Hagood’s men moved from the far right of Hoke’s line into Clingman’s former position on the far left.[xxiv]

The 51st North Carolina was posted behind Hagood’s brigade so they could support the South Carolinians, if necessary. After two days of hard fighting, the regiment was glad to be off the front lines. But the regiment’s soldiers were still not out of danger. A twelve-pound iron cannonball, skipping along the ground, losing its momentum as it neared the end of its trajectory, ricocheted, and hit Corporal John Blake of Company G squarely in the chest. The impact broke his collarbone and several ribs. It would take the corporal three months to recover from his wounds.

As the adversaries hurried to reinforce the southern ends of their lines, Lee instructed General Jubal Early to watch for an opportunity to turn Meade’s right flank. Hancock’s departure surprised Burnside, whose corps was entrenched immediately south of II Corps. The movement left Burnside’s flank exposed, and he decided to withdraw to a stronger defensive position. As the Yankee infantry began pulling back, “Old Jube” saw his chance. Early launched a furious attack on the withdrawing troops. Like the previous day’s attack, the Confederates made good progress at first, but the Union forces recovered quickly and stopped the Rebel advance.

Cold Harbor, Day 4

At precisely 4:30 in the morning on June 3, the three Union corps on the southern end of Meade’s line began moving toward the Confederate positions. The cancellation of the previous day’s attack had given the Rebel infantry time to construct formidable breastworks. Southern artillery occupied strategic positions that commanded the entire front. Lee’s army waited patiently for the Yankees to come into range.

As the Union infantry neared the Confederate works, they were mowed down by well-aimed canister. The leading ranks could not fall back because of the masses of infantry pressing behind them. Any of the Yankees that got within range of the Confederate trenches were slaughtered by musket fire. In less than an hour, the assault had failed with the attackers suffering thousands of casualties (estimates range from 3,000 to 7,000).

At seven o’clock, Burnside’s IX Corps belatedly attacked on the northern end of the Confederate line. The effort received half-hearted support from Warren’s V Corps. Burnside’s men drove in the Confederate pickets and quickly overran some of the enemy rifle pits. But then the attackers came within range of the Confederate’s main works. Well-directed artillery fire and a storm of rifle bullets caused the attack to sputter and then grind to a halt. Before Burnside could renew his assault, Grant ordered an end to offensive operations.

Aftermath

The Union soldiers began fortifying their positions. For the next nine days, the two armies sat facing each other, trading sporadic artillery fire and skirmishing occasionally. The 51st North Carolina lost one man killed, three wounded and one captured during this period.

After the fight on June 1, a correspondent for the Press Association reported that Clingman’s brigade had given way while being attacked by the Union infantry, and that “Colquitt’s Georgia brigade quickly came to its assistance, recovering nearly all the ground Clingman lost.”[xxv] This account was published in many of the major newspapers in the South.

Clingman was incensed. He fired off a letter, dated June 5, to the Richmond Dispatch, correcting the correspondent’s error. He explained that an unnamed brigade gave way, and the brigade’s withdrawal allowed Union troops to get on the flank and rear of the 8th and 51st Regiments. If the 8th Regiment, wrote Clingman, “had then given way, it might have escaped with much less loss.” The 51st Regiment “suffered in the same manner, heavily, because it continued to fight by facing in two directions.” Clingman ended his letter by asking the press to remember “next to his country, the true soldier values the reputation and glory of his own good actions.”[xxvi]

Heavy Losses in the 51st North Carolina

The flank attack on Clingman’s Brigade during the evening of June 1 cost the 51st Regiment dearly. One hundred twenty-two men, including Major McDonald, were captured. In addition to the captured soldiers, the regiment had sixteen killed and forty wounded. The total losses for the 51st North Carolina during the unit’s two days of fighting at Cold Harbor were twenty-six killed, sixty-seven wounded, and 131 captured.

Company I, holding the left of the regiment’s line, contributed nearly a third of the captured men. The company commander, Captain George Sloan, who had been wounded at Drewry’s Bluff, was among the men captured. The company’s first lieutenant, Joseph MacArthur, had been captured at Drewry’s Bluff. Second Lieutenant Charles Guy assumed command of the company.

Captain Walter Bell, commanding Company B, was seriously wounded during the first day at Cold Harbor. Company B’s first lieutenant was absent sick. As a result, command of the company devolved to Bell’s brother-in-law, Second Lieutenant Thomas Herring. Herring was wounded in the head during the desperate fighting on the 1st of June. The company’s third lieutenant had been captured at Drewry’s Bluff. The company would not have an officer on duty until the regiment’s sergeant major, Charles Cowles, was promoted to second lieutenant and transferred to B Company seven weeks after the battle.

Company D’s commander, Robert McEachern, was mortally wounded during the first day of fighting. Through an administrative error, First Lieutenant John Malloy was promoted to Captain. Malloy had been captured at Drewry’s Bluff. The company’s second and third lieutenants had also been casualties at Drewry’s Bluff. Company D would be without an officer until Private Francis Currie was promoted to Second Lieutenant six weeks later.

The three Mercer siblings of Company D were casualties. Miles and John were wounded by Yankee bullets. Miles lost his arm because of the wound. John was wounded in the leg and captured. He would survive imprisonment at Point Lookout and Elmira. The third brother, Saul, was not wounded, but he was captured. Saul died of dysentery at Elmira after only seven weeks of captivity.

Colonel McKethan, in a letter to his father a few days after the battle, summed up the fighting with this short statement, “We have had another great battle and repulsed the enemy with great slaughter. We lost heavily.”[xxvii]

[i] Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants 3 vols. (New York: C. Scribner’s sons, 1944) 3: 505.

[ii] Walter Clark, ed., Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65, 5 vols. (Goldsboro: Nash Bros., 1901) 5: 198.

[iii] Gordon C. Rhea, Cold Harbor: Grant and Lee May 26-June3, 1864 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002) 184.

[iv] Histories, 5: 198.

[v] The events of May 31, 1864 are compiled from multiple sources: Histories, 2: 516-517, 3: 512, 5: 197-205; Daily Confederate 8 Jun. 1864 and 17 Jun. 1864.

[vi] Rhea, 185-187.

[vii] Rhea, 190-191.

[viii] North Carolina Troops, 12: 268.

[ix] Histories, 5: 199-200.

[x] Official Records, Series 1, 36 (part 1): 996.

[xi] Rhea, 234.

[xii] Rhea, 235-237.

[xiii] Rhea, 238.

[xiv] Official Records, Series 1, 36: 671.

[xv] Histories, 5: 201.

[xvi] Histories, 5: 201-202.

[xvii] Rhea, 243-244.

[xviii] Johnson Hagood, Memoirs of the War of Secession (Columbia: State Company, 1910) 256.

[xix] Rhea, 246.

[xx] Histories, 5: 203; Rhea, 253.

[xxi] Official Records, Series 1, 36 (part 1): 671.

[xxii] Rhea, 249-250.

[xxiii] Rhea, 254-255.

[xxiv] Rhea, 264-265.

[xxv] Daily Confederate 8 Jun. 1864.

[xxvi] Wilmington Journal 9 Jun. 1864.

[xxvii] Weekly Intelligencer 7 Jun. 1864.

Copyright © 2021 – 2024 by Kirk Ward. All rights reserved.