“A portion of the enemy instantly, with loud cheers, charged up the hill toward the battery, and bore up steadily in the face of a well-directed and most destructive fire.”

-Colonel H. C. Lee, U. S. Army, describing the charge of the 51st and 52nd North Carolina Regiments at Goldsboro

“Their prompt and daring attempt furnished the highest evidence of their courage and readiness to obey orders.”

-General Thomas Clingman, CSA, referring to the same charge

The Plan

On November 7, 1862, a frustrated President Lincoln replaced General George McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln chose General Ambrose Burnside as McClellan’s successor. Burnside had shown promise as a corps commander, and Lincoln hoped he would be more aggressive than McClellan had been. Burnside, knowing that Lincoln expected immediate action, hastily devised a plan to capture Richmond.

Burnside planned to march the Army of the Potomac overland directly to Richmond and assault the Rebel capital. General John Foster, with a force of 16,000 men at New Bern, would simultaneously move toward Goldsboro and seize the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad. Foster’s attack on Goldsboro would deny supplies to the Richmond defenders and position Foster’s troops to block the Confederate army when it retreated southward from Richmond.

The Advance

Burnside’s army crossed the Rappahannock River at Fredricksburg on the 11th of December. On the same day, Foster left New Bern with 10,000 infantry, supported by 640 cavalry and 40 pieces of artillery. The Federals made slow progress, skirmishing with small groups of Rebels along the way. They reached Kinston on the 14th of December. There they met a much smaller Confederate force under Brigadier General Nathan G. “Shanks” Evans.1 The Union troops drove the Confederates off.

On December 13, the day before Foster reached Kinston, General Burnside was thoroughly beaten at Fredericksburg. The Army of the Potomac suffered 8,000 casualties that day in fruitless frontal assaults on the Confederate positions. Burnside retreated two days later, ending the fourth attempt for a quick and decisive campaign against Richmond.

The next day, after pillaging Kinston, General Foster’s force pushed on toward Goldsboro. Although Foster had received news of the Union defeat at Fredericksburg, he decided to continue the expedition. His troops were close to Goldsboro and had met light resistance so far. They might as well burn the railroad bridge across the Neuse River and then return to New Bern.

The Response

The Federals reached Whitehall on the morning of December 16 and once again beat off a small group of Confederates. While the Union troops were skirmishing at Whitehall, Confederate reinforcements started arriving in Goldsboro. General Thomas Clingman arrived in the morning with the 8th North Carolina. The 51st North Carolina showed up in the afternoon. Clingman positioned the two regiments at the point where the Whitehall Road crossed the railroad, about half a mile south of the river.

The 52nd North Carolina, detached from Pettigrew’s Brigade in Virginia, came into Goldsboro late that night. Upon arrival, the regiment was assigned to General Clingman. Clingman ordered the regiment to take a supporting position behind the 8th and 51st Regiments.

The next morning, Shanks Evans marched into Goldsboro with his brigade of South Carolinians. Evans ranked Clingman, so he assumed command of the forces in the area. He ordered Clingman to defend both the county bridge, a covered structure spanning the Neuse almost directly south of Goldsboro, and the railroad bridge, half a mile to the east of the county bridge.

The Battle

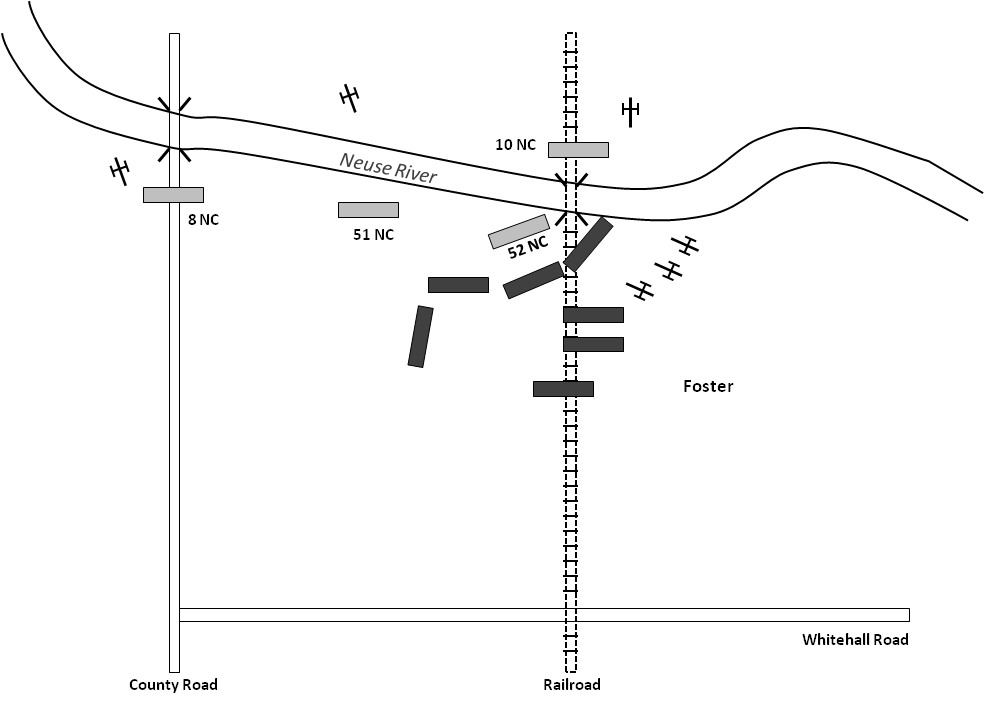

On the morning of December 17, Confederate scouts reported that Foster’s army was fast approaching along the Whitehall Road. General Clingman, unsure of Foster’s intentions, split his force to cover both the railroad trestle and the county bridge. Colonel James Marshall’s 52nd North Carolina marched up the tracks and took a defensive position next to the bridge. Colonel Shaw’s 8th Regiment, supported by a section (two guns) of artillery, moved to the county bridge and formed a defensive line there. The 51st Regiment, under Lieutenant Colonel Allen, was positioned near the river between the other two regiments.

The Union force approached the railroad bridge. Foster sent two regiments down the tracks to burn the structure. Four more regiments supported the advance, two to the right and two to the left of the railroad embankment. A final regiment trailed behind as a reserve.

As the Yankee infantry approached the river, three batteries of Federal artillery unlimbered and began shelling Marshall’s regiment and the bridge structure spanning the river. Some of the cannon fire was directed on the 51st Regiment, to the Union left. The Confederates responded with artillery fire from batteries on the opposite bank of the river and from a one-gun railroad Monitor.

General Clingman, seeing the devastating effect of the Union guns on the 52nd Regiment, ordered Lieutenant Colonel Allen to move the 51st Regiment toward the bridge and form a line of battle on Marshall’s right. While Allen’s regiment was moving toward the bridge, the Union infantry closed with Marshall’s regiment and turned its left flank. The Fifty-Second began hurriedly retreating up the riverbank and ran into the Fifty-First, coming down the bank. Mistaking Marshall’s men for Union infantry, the lead company of the 51st Regiment opened fire. Luckily, the volley was aimed high, and none of Marshall’s men were hit.

General Clingman got both regiments organized and led them back to the bridge. By then, all seven Union regiments were near the crossing, and their volleys, coupled with the intense artillery fire, drove the Confederates back up the riverbank. Clingman, deciding he could not defend the bridge with his small force, ordered all his troops to cross to the north side of the Neuse River at the county bridge.

After several unsuccessful attempts, the Yankees set the railroad trestle on fire. Satisfied that the fire would destroy the structure, the Union infantry withdrew a short distance and took up positions along the railroad embankment. All the Federal guns began firing on the bridge to aid in its destruction and to prevent the Confederates from attempting to douse the blaze.

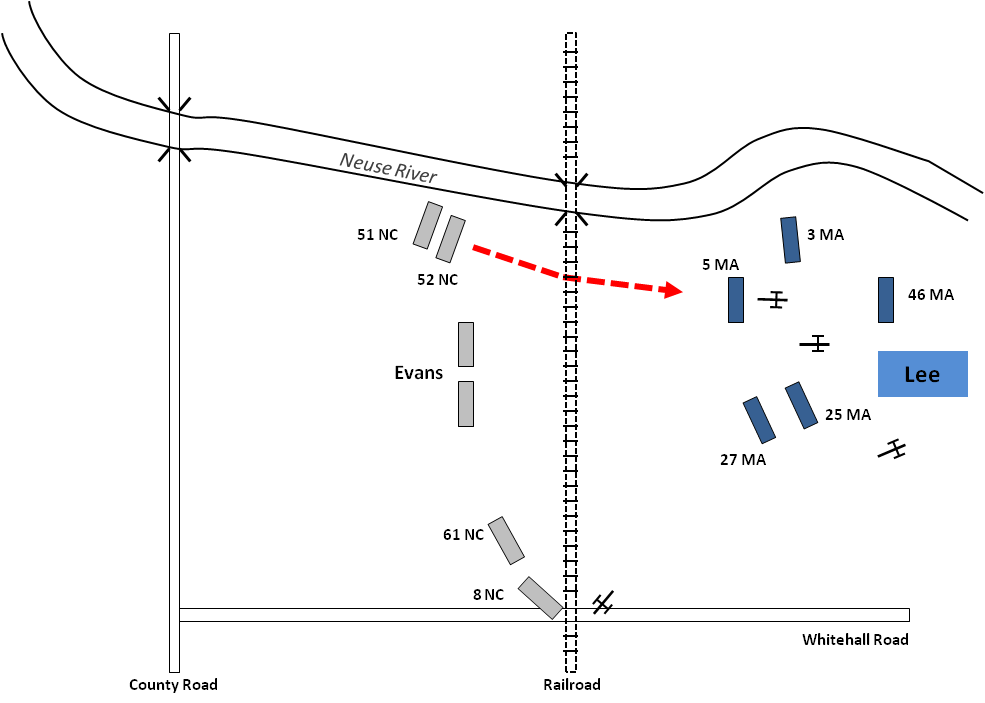

Meanwhile, the 61st North Carolina had arrived in Goldsboro. General Clingman now had under his command four regiments of infantry and a section of artillery. General Evans ordered him to attack the Yankees with his entire force. The North Carolinians crossed the county bridge to the south side of the river. Clingman led the 51st and 52nd Regiments down the riverbank to a position near the burning bridge.

Clingman positioned the two regiments in the edge of a wood near the river, some 500 yards from the railroad. He arranged the units into two lines, the 52nd Regiment in the lead, and ordered the men to lie down. Clingman then put Colonel James Marshall of the 52nd North Carolina in charge of the two regiments and instructed him to remain in position until he heard Confederate artillery open up on his right. When the guns started firing, the two regiments were to charge the Union infantry behind the railroad embankment. Clingman rode off toward the county bridge to position his other units on the right flank.

Convinced the bridge was destroyed, Foster ordered his artillery to cease fire. The Union force began to withdraw back down the Whitehall Road and onward to New Bern. Colonel Horace C. Lee’s brigade remained as rear guard for the withdrawal. Lee positioned a detachment of cavalry and an artillery battery of four guns on a hill east of the railroad, about 500 yards from the bridge.

Clingman led his other two regiments and the two artillery pieces down the county road to get on the left flank of the Union rear guard. Before Clingman could get the two regiments into position, General Evans arrived on the north end of the field. Dismissing Clingman’s plan to attack the Union forces on both flanks simultaneously, he ordered the 51st and 52nd Regiments to charge the Union position immediately.2 The two regiments hastily started across an open field, moving toward the railroad.

Colonel Lee had started his brigade down Whitehall Road to join Foster’s main body of troops. The Union artillerists, still on the hill to the east of the railroad, spotted the Confederates emerging from the woods. They opened fire on the Rebel infantry. Colonel Lee, alerted by the artillery fire, looked toward the bridge and saw several Confederate battle flags waving above the railroad embankment. He immediately halted his brigade and rushed another battery of artillery to the hill. Lee then hurriedly deployed his five regiments of Massachusetts infantry in support of the artillery.

Marshall’s men, hurried along by Union shrapnel, reached the railroad. They paused in the cover of the embankment and redressed their lines. Once organized, the men climbed the embankment and charged, screaming the Rebel yell. As the Confederates got nearer, the Union guns let loose with loads of canister, mowing down the advancing ranks.

The Rebel charge slowed, then halted approximately 300 yards from the Union line. Colonel Marshall looked at the ten guns on the hill supported by ranks of Union infantry and decided to call off the attack. He ordered a withdrawal. The North Carolinians began a “precipitate retreat” back to the railroad.

As the men of the 51st and 52nd Regiments ran for the safety of the railroad embankment, Clingman’s other two regiments finally got into position. The sole artillery piece (the other had fallen into a ditch) began firing on the left of the Union line. The Yankees unlimbered a third battery and returned fire. The 8th and 61st Regiments moved forward in support of the lone gun but withdrew quickly when the Union artillery zeroed in on them.

As Clingman’s units on the right broke off their engagement with the Federals, Shanks Evans’ brigade emerged from some trees to the west of the railroad. The brigade had been sheltered in a stretch of woods running parallel to the railroad track, slightly south of the 51st and 52nd Regiments. As the Rebel infantry approached the embankment, they were fired on by one of the Union regiments in the center of the Federal line. Evans’ men pulled back into the trees without returning fire.

Receiving no more challenges from the Confederates, Colonel Lee put his brigade on the road. They shortly joined General Foster’s main column. Foster resumed his march toward New Bern, arriving at his base four days later.

The Result

In their first battle, the men of the 51st North Carolina fought valiantly, even though they were driven from the field twice. When the unit, with the 52nd Regiment, engaged at the Goldsboro Bridge, they were being blasted by sixteen field pieces while facing an infantry force more than three times their number. Both regiments were forced to withdraw by overwhelming fire.

Despite the fierce fire the men of the Fifty-First were subjected to at the bridge, they willingly returned to the field a few hours later to mount a counterattack against the enemy. They charged a superior force, supported by artillery, over 300 yards of open ground before being thrown back. Their heroic action cost them many casualties. General Clingman, in his report after the battle, conjectured that the vast majority of the regiment’s losses during the battle were sustained during the failed charge.

The official casualty report for the 51st Regiment’s engagement at Goldsboro was five killed, fifty wounded, and five missing. One of the wounded died in the hospital at Goldsboro on the 31st of December, and two more wounded soldiers died in January. The regiment’s muster rolls, as summarized in North Carolina Troops, indicate six men were missing instead of five. The missing men were all likely captured; all of them were present for duty in January. Foster, not wanting to be slowed down by prisoners, paroled all his captives within twenty-four hours of the engagement at Goldsboro Bridge. The parolees were exchanged on January 10, 1863.

1 Evans earned the nickname “Shanks” while a cadet at West Point because of his spindly legs. A hard fighter and equally hard drinker, Shanks was court-martialed and acquitted for being drunk during the skirmish at Kinston.

2 Lieutenant John Robinson of the 52nd North Carolina later commented, “Under General Clingman’s plan of attack there was a possibility of successfully dislodging the enemy. Under General Evans’ order the attack was simply reckless disregard for the lives of his troops.”

Sources

John G. Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1963) 139, 144.

Walter Clark, ed., Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65, 5 vols. (Goldsboro: Nash Bros., 1901) 1: 519-520, 3: 230-231.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series 1, 53 vols. (Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1880-1905) 18: 54-122.

Wilmington Journal 8 Jan. 1863, 15 Jan. 1863.

Copyright © 2021 – 2026 by Kirk Ward. All rights reserved.