NOTE: During 1865, the 51st North Carolina was attached to Clingman’s Brigade which was assigned to Hoke’s Division. Few records exit for the regiment in 1865. Detailed casualty numbers are unavailable.

Sherman Invades North Carolina

On March 14, Sherman’s army left Fayetteville after thoroughly ransacking the town. The army was moving in two wings of 26,000 men each. The eastern (right) wing was commanded by Major General Oliver O. Howard. Howard was moving his force toward Goldsboro. The western (left) wing, commanded by Major General Henry Slocum, headed toward Raleigh.

General Joseph Johnston, who was assembling a force of about 19,000 men, knew he could not take on Sherman’s entire army. But with the Union force split into two parts, he saw an opportunity to defeat one wing. To do so, he needed time to assemble his scattered forces, and he needed to know Sherman’s destination. Were the Yankees going to plunder Raleigh, or would they head to Goldsboro for provisioning?[i]

In order to buy time and to better ascertain Sherman’s intentions, Johnston ordered General Hardee and his mixed bag of 5,000 troops to delay Slocum’s wing of the army. Hardee chose a defensive position near Averasboro and waited for Slocum’s left wing to arrive. On March 15, the Union advance guard ran into Hardee’s skirmishers. The next day, the Federals attacked in overwhelming numbers. Anticipating the attack, Hardee had established three defensive lines. These lines prevented the Yankees from quickly overrunning the small Rebel force. Hardee executed a fighting retreat that delayed Slocum for a day. That night, Hardee’s men slipped away to the north and made camp. General Hardee intended to rest his men for a few days, but the next day, Johnston ordered him to join up with the Confederate forces converging on Bentonville.[ii]

Howard’s right wing continued marching toward Goldsboro as Slocum pushed Hardee’s small blocking force out of the way. Johnston estimated that the two wings were a day’s march apart.[iii] He now felt confident in striking the left wing. Bentonville sat astride Slocum’s path to Goldsboro, and the terrain there was favorable for an ambush.

Johnston Springs His Trap

At sunrise on March 19, Slocum’s foragers ran into General Wade Hampton’s cavalry pickets near Bentonville. A brief skirmish ensued. Slocum thought the cavalry was simply harassing his advance. He sent General William Carlin’s division of the XIV Corps up the road to clear the cavalry out of the way. Carlin deployed his three brigades in line of battle and moved them up the road, the Confederate cavalry withdrawing before them.

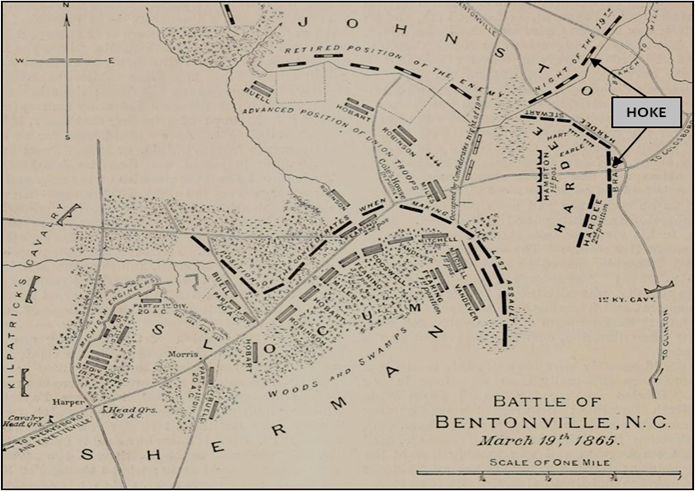

Johnston had deployed his forces early that morning. Hoke’s division was placed in the path of the Union advance. The division was behind hastily constructed earthworks with its right flank resting on the Goldsboro Road. Clingman’s brigade was in reserve, behind and to the right of Hoke’s line. General Alexander Stewart’s corps was placed to the right and front of Hoke. Stewart’s line was almost at a right angle to Hoke’s earthworks and ran parallel to the Goldsboro Road. These troops were placed at the edge of a wood that hid their position. Hardee’s corps was supposed to be between Hoke and Stewart, but it had been delayed en route and had not arrived by the time the fighting started.

As Carlin’s brigades pushed the Confederate cavalry back, they were suddenly hit with a blast of musket fire from Hoke’s division. At the same time, Confederate artillery opened on the advancing Federals. The Union brigades withdrew and waited for orders. General Carlin surveyed the situation and sent two brigades northward to get around Hoke’s right flank. These brigades advanced to within fifty feet of the trees where Stewart’s hidden men waited. Stewart’s soldiers unleashed a murderous fire. The Union troops showed remarkable courage. Instead of retreating, they charged the Confederate line. Hand-to-hand combat followed while the Confederates continued to blast away at the Yankee infantry. After a few minutes the two Union brigades broke and fled.

Carlin’s remaining brigade attacked Hoke’s line repeatedly. General Bragg became alarmed at the persistence of the enemy assaults. Convinced that Hoke’s soldiers could not hold their position, he sent an urgent request to Johnston for reinforcements. Major General Lafayette McLaws’ division of Hardee’s corps was just arriving, and Johnston sent the division around the rear of the Confederate lines to the far left of Hoke’s position. The terrain was difficult, slowing McLaws’ advance. By the time McLaws reached his assigned position, Hoke’s veterans had beaten back the Union assault.

The battle paused. The Union troops were content to wait for reinforcements and began entrenching. Johnston was reluctant to press the enemy until Hardee’s other division arrived. The two sides sat in place, occasionally firing volleys at each other. During the lull, Union General James Morgan’s division arrived on the field. Morgan, being under no pressure from the Confederates, put his men to work constructing a log breastwork. Working feverishly, the Yankees constructed a crude, but formidable, “fort” within two hours.[iv]

Hardee’s remaining division, commanded by General William Taliaferro, finally showed up around two o’clock. These men were rushed to the extreme right of the Confederate line and put into line of battle. At 2:45, Johnston ordered an all-out attack against the Yankee infantry. The right wing of Johnston’s army surged forward and quickly scattered three Union brigades. Bragg held Hoke’s division back while the left of the Union line crumbled.

The right wing’s charge had become scattered and disorganized while chasing the fleeing Yankees. Hardee halted the Confederate brigades and began realigning them. As Hardee paused, Bragg finally decided to send Hoke’s men into the fray. Hoke started pushing his division through a gap in the Union lines to the left of Morgan’s position, hoping to cut off the remaining Federals to his north. Union infantry, seeing Hoke’s division storming into their rear, began abandoning their trenches. Many of the Yankee soldiers, their escape route blocked, began surrendering.

Bragg, however, had different ideas. Buoyed by the right wing’s success, he ordered a direct assault on Morgan’s improvised fort. Hoke stopped his flanking movement and sent his brigades forward in a charge against Morgan’s division. Morgan’s men, well rested and behind their log walls, stubbornly repulsed Hoke’s assault, throwing the Confederates back with heavy losses.[v] With the threat from Hoke neutralized, the Union infantry that had begun to surrender hurriedly reoccupied their works.[vi]

As Hoke retired to his lines, Hardee began attacking Morgan’s position from the rear. While the Confederates focused on attacking Morgan’s division, the Union left was reinforced by Major General Alpheus Williams’ XX Corps. One brigade of the corps struck the Confederates in the rear as they formed to attack Morgan’s men yet again. The attack sent the Confederates scrambling back.[vii]

Around 5:30, Taliaferro rallied enough men to resume the attack on the Federal left. But it was too late. The Yankees were well fortified and had brought up twenty-six guns for support. The Confederates were mowed down. After repeated attacks failed, Johnston ordered his troops back to their original positions.[viii] The frazzled Confederates ended the day in the same positions they occupied when the day began. There were a lot less of them now.

Days 2 and 3: The Combatants Settle for a Draw

The next day, just after sunrise, the first division of Howard’s wing arrived at Bentonville. The Federals skirmished with Hoke’s division, and the Confederates withdrew. Hoke bent his line backwards in a curve to the left (the 51st North Carolina was positioned near the center Hoke’s new line). Johnston’s lines were now a semicircle with each end anchored on Mill Creek. Johnston held this position while he evacuated his wounded across the only bridge available.

The two sides skirmished off and on during the day, with the heaviest firing occurring in Hoke’s front.[ix] Neither army was anxious to resume the lively activities of the day before. The antagonists were content to fight at a distance for the rest of the day. By nightfall, only a small part of the Confederate wounded had been removed. Johnston decided to remain at Bentonville one more day so he could complete the evacuation.[x]

When March 21 dawned, Sherman was surprised to see Johnston’s army still holding their positions. Sherman was not in the mood to take on Johnston’s veterans. The Union general did not feel that Johnston presented a real threat to his army. Sherman saw no benefit in wasting blood on defeating his enemy.

The two armies continued to stare each other down for another day. Other than scattered skirmishing, the morning was quiet. In the afternoon, a sudden rush by Major General Joseph Mower’s division through Johnston’s lines threatened to take the sole bridge across Mill Creek. Loss of the bridge would have cut off Johnston’s only avenue of retreat. If the Yankees destroyed the bridge, Johnston would have to surrender his army.

Parts of several Confederate infantry and cavalry units hit Mower’s division from all sides. Mower’s assault came to an abrupt halt. At about that time, Sherman ordered Mower to break off his attack and return to the Union lines. Mower grudgingly complied and pulled his division back to its position facing the Confederates.[xi]

That night, Johnston completed the evacuation of the wounded and started pulling his army back across the bridge. In the morning, the Union soldiers looked with relief at the empty trenches in their front. Sherman sent a brigade of infantry in pursuit. This brigade skirmished twice with Wheeler’s cavalry before giving up the chase. The last Civil War battle in the East was over.

Casualties

Hoke’s division was heavily engaged at Bentonville. The division suffered 61 killed, 471 wounded, and 202 missing.[xii] Clingman’s brigade lost three killed, thirty-six wounded, and two missing.[xiii] The exact losses of the 51st North Carolina are unknown, but during March 1865 the regiment documented one killed, seven wounded and twenty-two captured.

One of the Fifty-First’s wounded, Private David McLean of D Company, was hit by a “Minnie [sic] ball striking the top of the head rendering him senseless.” Private McLean survived the wound, but he suffered with “defective eyesight and hearing” the rest of his life.[xiv]

Bragg’s Final Failure

Bungling Braxton Bragg had once again displayed his talent for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. His panicked call for reinforcements that he did not need, his failure to coordinate his attacks with those of Hardee, and his ill-advised decision to order a frontal assault on Morgan’s log fort contributed greatly to the Confederate failure at Bentonville.

Writing about Bentonville after the war, Confederate General Wade Hampton stated that the movement of McLaws’ division to the far left was the only error General Johnston made during the battle. Hampton felt that had McLaws immediately joined Stewart’s corps in a counterattack rather than wasting hours tramping to Bragg’s relief, the entire Union XIV Corps would have been routed. Johnston, in his memoirs, called the decision to shift McLaws’ division “injudicious.”

Hampton also contended that Bragg disregarded Johnston’s orders to support Hardee’s assault. Johnston had ordered Bragg to turn his troops to the left, which would have aligned Bragg’s corps with those of Stewart and Hardee. This alignment would have allowed Bragg to turn the Federals’ right flank as Hardee and Stewart assaulted the Union left.[xv]

Bragg’s third error that day was perhaps his worst. Hoke’s division had penetrated the Union lines and was in the process of pushing the enemy infantry out of their trenches when Bragg ordered the direct assault on Morgan’s fortifications. Bragg was not even on the field when he issued the order. General Johnson Hagood, commanding a brigade in Hoke’s division, wrote, “The loss in our division would have at least been inconsiderable and our success eminent had it not been for Bragg’s undertaking to give a tactical order upon a field that he had not seen.”[xvi]

Bragg, at his own request, was relieved of command.

[i] Weymouth T. Jordan, Jr., The Battle of Bentonville (Wilmington: Broadfoot Publishing, 1995) 13.

[ii] John G. Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1963) 326.

[iii] Barrett, 325.

[iv] Jordan, 18.

[v] Barrett, 334-335.

[vi] Official Records, Series 1, 47 (part 1): 1091.

[vii] Jordan, 19.

[viii] Jordan, 20.

[ix] Daniel W. Barefoot, General Robert F. Hoke: Lee’s Modest Warrior (Winston-Salem: John F. Blair, 1996) 300.

[x] Jordan, 23.

[xi] Jordan, 23.

[xii] Official Records, Series 1, 47 (part 1): 1060.

[xiii] Official Records, Series 1, 47 (part 1): 1080.

[xiv] Daniel McClean, North Carolina Pension Application, 19 Jun. 1902.

[xv] Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 4 vols. (New York: The Century Co., 1887-1888) 4: 703-704.

[xvi] Johnson Hagood, Memoirs of the War of Secession (Columbia: State Company, 1910) 360-361.

Copyright © 2021 – 2026 by Kirk Ward. All rights reserved.